The impacts of the climate crisis on the health and ancestral knowledge of Indigenous women

By Rudja Santos from Carta Amazônia

Edited by Méle Dornelas

As COP30 brought the Amazon to the center of global discussions on the climate crisis at the end of 2025, the daily lives of Indigenous women reveal a dimension still largely absent from official debates: environmental changes have profoundly altered the rhythm of the forest—and with it, the rhythm of life. Increasingly unpredictable rainfall, prolonged periods of extreme heat, river instability, and the scarcity of medicinal plants are impacting traditional agricultural practices and ancestral forms of community care. These imbalances directly affect the physical and emotional health of women, exacerbating longstanding vulnerabilities already present in Indigenous territories.

According to Marinete Tukano, the General Coordinator of the Union of Indigenous Women of the Brazilian Amazon (UMIAB)—a network that brings together women leaders from different peoples across Brazil’s Amazon region—the main impacts of climate change on Indigenous women’s health are related to mental health, food sovereignty, agricultural harvests, family economies, and violence.

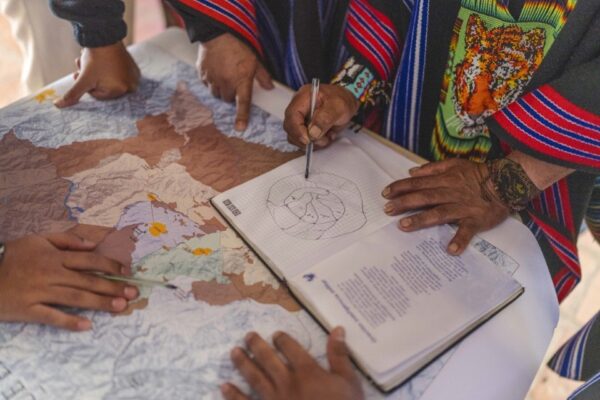

The Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) closely follows these transformations through initiatives developed in Brazil and Colombia focused on Indigenous women’s health. These efforts reinforce Marinete’s understanding of how the climate crisis has direct impacts on nutrition, daily life, emotional well-being, safety, and the lives of Indigenous women.

The Impacts and Consequences of a Sick Climate

The loss of cultivated fields, river siltation, and declining fish stocks—associated with deforestation and environmental degradation—are directly linked to factors that undermine food sovereignty and, consequently, the integrity of health. Women report symptoms such as dizziness, weakness, and weight loss, resulting from increasingly insufficient diets.

These impacts are also reflected in daily work routines. Tasks have intensified. Women walk longer distances to collect water when rivers run low, spend more hours in their fields to secure minimal harvests, and take on the care of sick people in regions where malaria, dengue, and respiratory illnesses advance with rising temperatures. This accumulation of responsibilities directly affects physical and emotional health.

Recent research, such as a study by the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), indicates that Indigenous women in Brazil die at younger ages than other population groups. These findings highlight how structural inequalities, environmental racism, and climate change intertwine, producing severe impacts on their bodies and ways of life. Marinete illustrates these data by noting that malaria, malnutrition, mental illness, suicide, and cancer are among the greatest threats to Indigenous women’s lives.

The climate crisis also interferes with the natural rhythms of the forest. Indigenous leaders such as Olga Macuxi (Roraima, Brazil) and Sineida Garreta (Putumayo, Colombia), along with ACT analysts Sandra Patiño and Lirian Ribeiro, describe a recurring perception: the forest’s calendar is out of sync. Plants no longer grow at the right time, roots lose strength, traditional medicines take longer to work; and global warming disrupts forest cycles and even birth patterns. “Rising temperatures are associated with an increased risk of premature births,” explains Lirian, ACT-Brasil’s focal point for Indigenous Medicines and Women.

In hospitals, another recurring obstacle confronts pregnant women: obstetric and institutional violence. There is a lack of interpreters, little respect for rituals and ancestral care practices, and many midwives—central figures in Indigenous care—are not allowed to accompany women during childbirth. For many cultures, this represents not merely discomfort, but a rupture of their own ways of bringing life into the world. There are frequent reports of women being treated without adequate consent, being isolated from their families, or being prevented from observing essential postpartum rituals.

Solutions, Pathways, and Futures

In the face of these challenges, Indigenous women’s movements, networks, and partner organizations have been building their own responses. As an example, Lirian points to initiatives developed by ACT in partnership with Indigenous women, including strengthening networks such as UMIAB; training workshops to consolidate knowledge; and support for women’s leadership in political spaces and actions, with the aim of influencing policies related to the health of their bodies and territories. Indigenous leaders emphasize, however, that without public policies that integrate traditional knowledge, health, and climate, these efforts will not be sufficient.

Marinete stresses that solutions must also strengthen multiple dimensions of women’s daily lives, including investments in socio-economic initiatives, the bioeconomy, and continuous healthcare programs—essential in the face of climate change. She also highlights the importance of Indigenous organizations taking the lead in responding to the crisis:

“In the current context, we are seeking to strengthen regional organizations across the Brazilian Amazon so that we can develop strategies together, seek partnerships, and be present in spaces of decision-making and climate debate.”

In the field of institutional health, Sandra highlights solutions such as intercultural protocols in Colombia, shared care pathways with hospitals, joint decision-making spaces, and the translation of informed consent documentation into Indigenous languages. She also emphasizes that these protocols must genuinely recognize the role of midwives rather than merely tolerate their presence.

Wisdom, Meaning, and Healing

Indigenous women say that they carry the climate in their bodies. They feel the changes in their skin, their breath, their fields, and the water they fetch every day. In the face of violence, food insecurity, and a territory where natural rhythms have been disrupted, they continue sustaining life in the forest—guided by traditional songs, prayers, and a persistent commitment to defending ancestral balance. “The forest speaks, and when it changes its tone, we need to listen,” says Olga Macuxi.

Confronting the climate crisis requires more than environmental targets: it demands recognition that the crisis passes through human bodies. When the climate is disrupted, the body of the Indigenous woman is also disturbed. Any policy that seeks to respond to the climate crisis must include Indigenous women as primary subjects, not merely as beneficiaries. Protecting the climate necessarily means protecting the bodies, minds, and lives of these women.

Don’t miss these powerful stories and updates. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.