September 25, 2020

By Juliana Jaimes

For more than a year, the indigenous peoples of the Curare Los Ingleses and Manacaro reserves in the lower Caquetá River region have been carrying out a weekly census of the species that exist in their territory. This is work historically reserved for men.

The expedition that the indigenous community of Manacaro carries out three times a week along the lower Caquetá River, in the Amazonas department, begins at eight in the morning. Twelve kilometers must be navigated by boat, always bringing two important items: a pencil and paper. All the tapirs, macaws, monkeys, turtles and caimans that are seen in or out of the water are recorded in a table that describes the type of species, the coordinates, and the number of individuals found. A little more than a year ago, this task of going out to protect and identify the animals that inhabit the forest, traditionally carried out by men, found new allies: women, who in addition to fulfilling their historic role, are now also guardians of biodiversity in the Amazon.

The main objective for the monitors is to observe. It is a task on which both protection and survival depends—not only for the animal species that inhabit the forest, but also for the indigenous people in voluntary isolation who, since the era of rubber slavery at the end of the 19th century, decided to end all relations with the greater society, including that with their neighbors. Any canoe, human footprint, hunter or fisherman that does not belong to the community must be reported. This is a job that the local indigenous elders have said “is very onerous, requires a lot of strength, and must be performed by men,” explains Lina Castro, an environmental education specialist at the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT).

But this has changed progressively, and without planning, thanks to the assistance of ACT in the process of reshaping the environmental management plan that first was drafted in 2012 in the Curare Los Ingleses reserve. The organization arrived with a clear idea to include women in the meetings and expand their activities beyond the domestic arenas of cultivation, cooking, and family that they have traditionally occupied. “We wanted to move the discussions from the mambedero (a coca-chewing ritual environment), where traditionally only men are. The integration came about in a very organic way. They (the women) began to get involved in activities like the expeditions,” adds Daniel Aristizábal, coordinator of ACT’s Isolated Peoples and Lower Amazonas program.

By 2014, in methodology workshops, trainings, and political meetings, the women were able to express their opinion and even dared to assume an increasingly leading role within proactive territorial protection. So much so that they increased their participation in the shifts and expeditions of one of the most important guard posts, due to its rich biodiversity and spiritual importance: Puerto Caimán, a central point that marks the border with the territory of voluntarily isolated peoples, for which it is strategic to prevent the entry of threats such as loggers, commercial fishing, missionaries, and outsiders in general.

Those who offer to be monitors in Puerto Caimán must go live for a whole month in a cabin deep in the forest, where they must cultivate food, fish, and monitor the checkpoint. “The women who go usually leave someone in charge of their children and their house. They must decide between the traditional tasks of women and spending a month learning about local species and doing other work that they consider important,” says Camila González, from ACT’s Lower Amazonas team.

Regionally, the Puerto Caimán ecosystem is among the most important for animal reproduction. It is a territory with salt licks where tapirs, pigs and deer visit to ingest minerals that are not found elsewhere in the forest. Pink dolphins can easily be seen in the lake in this area, and it is a breeding ground for species such as the black caiman, and the arawana and pirarucú fish, the latter being the largest freshwater fish in the world. It is also the habitat of the critically endangered giant otter and charapa turtle, according to the Colombian branch of the IUCN.

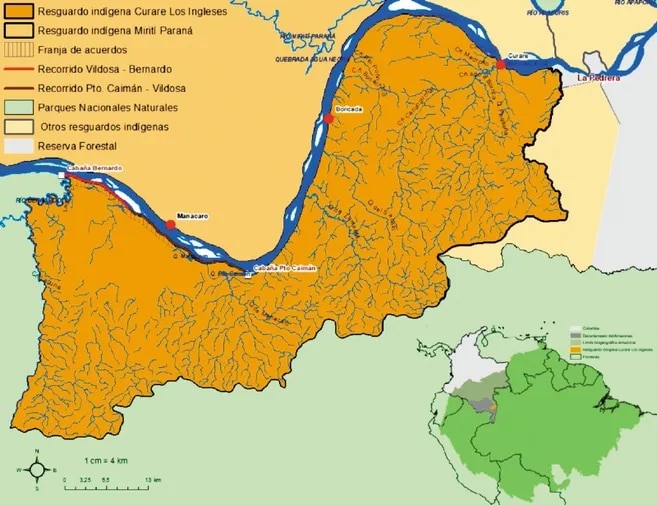

As in Curare, the participation of women in the expeditions of the neighboring Manacaro community also increased. There, indigenous women assumed 99% of the expeditions between 2017 and June 2020. According to ACT, of the 408 expeditions in the last four years, 404 have been led by women. The process between the two reserves began by establishing agreements for the management and use of natural resources. Expeditions are carried out across a total area of 35 kilometers. The Curare community monitors 23 kilometers from Puerto Caimán to the Vildosa creek, and the Manacaro community monitors 12 kilometers from this creek to the mouth of the Bernard River. On a monthly basis, the communities meet, share what is observed, and jointly analyze what has been recorded for decision-making purposes.

Natural leadership

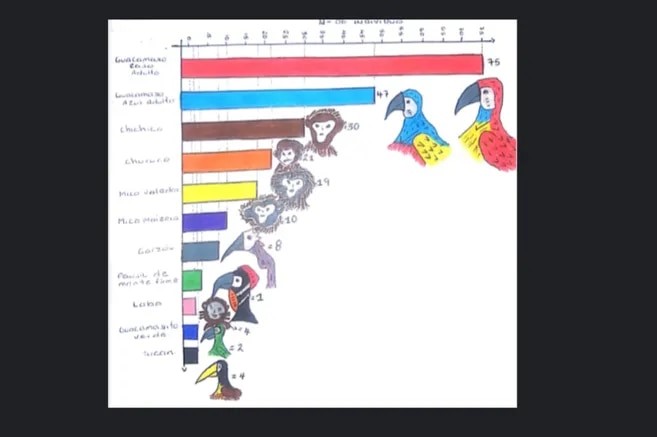

Over time, and thanks to the training that the women received in monitoring and surveillance techniques, such as cartography and GPS, the logs of the weekly expeditions became an analysis of the behavior of the species in the territory. “The women intuitively began to record how many animals they had seen and at what coordinates in order to compare that with the results of the previous month. It was their project, and we only supported them from a technical standpoint,” adds Camila González.

All records from the expeditions of the Curare and Manacaro reserves are sent monthly to ACT and the Colombian National Parks System. They digitize the results and analyze the species frequency or the potential threats that could affect them. “It was very gratifying for us to see that since we taught them to make graphs, the reports now contain that information, and this is important because they no longer have to wait a year to know what is happening in the territory, but rather when performing monthly analyses, they can begin to identify what is happening with regard to biodiversity,” adds Lina Castro.

The ownership of the activity assumed by the women has been such that now it is these women who ask the organization defending the Amazon to teach them things that they need to better carry out their expeditions. “One day, they asked us to conduct a workshop to learn how to operate the outboard motor in case they got stranded in the middle of the river. These motors are something that normally only men, who are traditionally in charge of transportation, know how to use. These are things that only those who are in the territory perceive the need to learn,” says González.

Today, four years after the arrival of ACT to assist with the environmental management plan, the women have developed much more confidence in their instincts in aspects which they were not traditionally involved. So much so that in mid-2020, they were motivated to submit a proposal to a call for Women Caregivers of the Amazon from the Amazon Vision program of the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development. “The response was almost immediate. They are not so shy anymore. We gave them the courage to understand that they could write and be responsible for money, and they lost their fear to apply for other projects,” concludes Lina Castro.

Within the indigenous worldview, women have always been fundamental to maintaining balance within the community. Their role as caregivers, as givers of life, and as those responsible for food sovereignty, through crop management and traditional seed conservation, is essential for indigenous governance. Now, their voluntary participation in territorial protection processes and their interactions with external actors, such as with ACT, has amazed many through their highly proactive attitude. Today the inhabitants of the Amazon have proudly discerned the birth of a new societal role deep within their rainforest.

Media Relations

For press release inquiries, please contact us at info@amazonteam.org.

Related Articles

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.