By María Fernanda Lizcano / March 13, 2023

- Families from the Bajo Caguán (lower Caguán River region), in Colombia’s Caquetá department, have implemented agroforestry and silvopastoral systems as a strategy to recover soil degraded by extensive cattle farming.

- 36 farms in this Caquetá territory, where one of the nation’s largest deforestation centers is located, have not practiced logging since 2017, have created connectivity corridors over at least 42,000 square meters, and have planted 33 hectares of agroforestry systems.

“When I was young, my dad gave me a chainsaw, and I felt like a man knocking down the forest. My dad’s pride was teaching me that. But now I tell my son, ‘You will not do what I did, you are going to take a shovel and plant a little tree. You will repair the damage that I caused,’” reflects Gerardo Patiño, while pointing to the forest in front of him that is part of his Los Guayabales farm, in the village of La Primavera of the municipality of Cartagena del Chairá, Caquetá. It rains heavily at the end of February, and Patiño celebrates the downpour, trusting in the power of water to make the trees he planted on his farm in 2022 grow. The drought, which lasts a little longer each year, finally yields. Gerardo Patiño went from felling “montaña”, as they call the forest in this territory, to reforesting with timber and fruit trees. His farm is one of 36 in the Bajo Caguán region—which occupy almost 3,500 hectares—and of 500 that exist in the entire department of Caquetá that have made conservation agreements and have promised not to log again. “They say that the animals are harmful, but no, we are the harmful ones. We cut down the places where the animals live, we leave them without the trees that provide them with food, and then we get angry because they do damage,” says Patiño, pointing to a small sugarcane crop that he has planted, and where from time to time a troop of monkeys come to eat stalks and experience the sweet taste of that plant.

Changing the mentality has not been easy. Four years ago, a team from the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) entered this distant territory that can be reached in five hours by boat—when the river allows it— from the urban area of Cartagena del Chairá. They came to develop the “Save Chiribiquete” project, also locally called “Agroforestry for Sustainable Production”, which began in 2017 in other areas of Caquetá but took time to arrive in the Bajo Caguán.

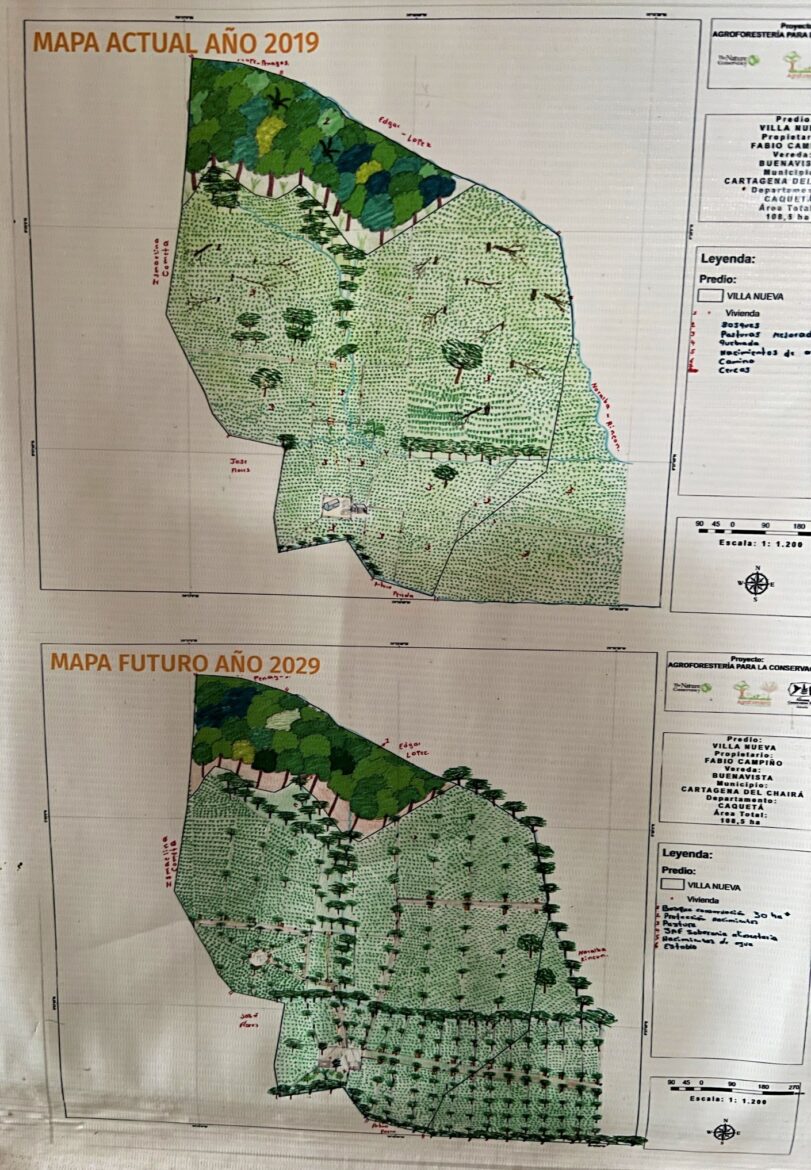

This initiative, based on property planning—which is developed with the families themselves—seeks to convert landscapes that were degraded by the situation of pastures in forests. This transformation is not a small thing, especially in this territory, which contains one of the largest centers of deforestation in the country. Per the latest annual report from Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (IDEAM), in 2021, 174,103 hectares of forest were lost in Colombia, an area that is almost equivalent to the size of the city of Bogotá; of these, 19% were in the Bajo Caguán.

Patricia Navarrete, coordinator of ACT’s Caquetá work, explains that boats with hundreds of calves arrived in that area of the country; these were sent by people outside the territory so that the peasant farmers would raise them. So, to maintain the cattle, the forest was cut down and burned, grass was planted, and huge pastures were established, which later, with the passing of time, lost their productivity due to soil erosion after the constant trampling of the cows. This created a vicious cycle: more trees had to be felled in order to plant new pasture.

The first thing that ACT did when they arrived in the territory was to listen to the peasant farmers and tell them that there was another way to work the land, to ensure food sovereignty and, principally, to contribute to the reduction of deforestation. Since livestock raising is the main livelihood of these families, and the peasant farmers still do not have alternatives that could provide them with sufficient income, ACT staff proposed that they implement agroforestry and silvopastoral systems—that is, small pastures, with introduced divisions, and with sustainable production trails that are 10 to 15 meters wide and contain scattered trees that function as stations for birds and as nexuses for the biodiversity of the area. “Then,” explains Navarrete, “When the grass in the first pasture runs out, the cows move to the next, and then to the next. When they return to the first one, the grass is already fresh.” Thus, the soil does not deteriorate and the need to chop down the forest is reduced.

The division of pastures was the best way to convince them to create connectivity corridors for wildlife, to implement agroforestry systems, and to isolate water sources, since the cows usually drink water and relieve themselves directly in the streams. They took the farmers to San José del Fragua, Doncello and Belén de los Andaquíes to show them what dozens of farms from other municipalities of Caquetá were doing. They say that they could not believe what they saw: 10 cows (or more) in pastures of 1,000 square meters (or fewer), farms with aqueducts, solar energy 24 hours a day, and the commercialization of bananas, lemons and other fruits they had grown in their new polyculture plots.

Alfonso Poveda, from the Miravalle farm, was one of the most skeptical. He thought it impossible to divide pastures with live fences. “I thought they were crazy, putting cows in a single plot,” he says. He wanted to do the opposite, and developed the pastures his way, but afterwards he realized they were right. Now the pasturage is plentiful. He has discovered a new appetite for planting trees, and already has a plantation of cacay (Caryodendron orinocense), açaí (Euterpe oleracea), peach palm (Bactris gasipaes) and other trees. He still does not fully understand how everything changed: “Fifteen years ago, the farm that was worth the most was the cleanest [the one with the fewest trees].”

He now goes out to tour his plantations, and presents his orchard with satisfaction. He is proud of one of his cacay trees, which has grown rapidly thanks to his learning to fertilize the soil. He taught Edgar Núñez, a zootechnician and field support specialist responsible for ACT’s Bajo Caguán process, the person who trains the farmers and who travels to the area every month to provide support and technical advice. Núñez is from Caquetá. He toured the farms on foot for hours, and today it is clear to him that restoration cannot be carried out with ranchers without offering them alternatives: “I cannot ask them to isolate the water if we do not install drinking basins for the cows. We are looking for strategies to effect restoration.”

50/50 model

Extensive livestock farming affects not only the soil but also the water sources. In the final evaluation of the physicochemical parameters of the water carried out by ACT in 2022, they determined that the quality was “regular” and “very bad” in 90% of the streams from which the farms are supplied (for both consumption by cows and human consumption). Contamination is generated primarily by cattle feces and urine. This analysis was also carried out through the monitoring of aquatic macroinvertebrates, organisms that are present in the water when it is clean and healthy.

Because of this problem, the 36 farms in the Bajo Caguán have had electric pumps installed that work with solar panels, elevated tanks, and aqueducts for livestock and human consumption. The pastures have their drinking basin, and the farmers finally have solar energy on their land. Additionally, the farms have reforested and isolated a combined 6.6 kilometers of land along the banks of water sources, and have planted nearly 42,000 square meters of connectivity corridors, 32,000 linear meters of live fences, and 33 hectares of agroforestry systems.

“We know that deforestation causes environmental damage, but the worst thing is the fragmentation of the forest, which is the reason,” adds Núñez, “that we are looking for is to connect one forest with another and generate connectivity corridors so that the species can travel again.” He remembers, between laughs, that one of the farmers engaged in the project was told that he was crazy for planting trees, especially in the middle of summer. To prevent the others from being right, he put himself in charge of watering them every night, without anyone seeing him. That man is Albeiro Camacho, from the Los Naranjales farm, a neighbor of Gerardo Patiño, with whom he is building a connectivity corridor 270 meters long by 20 meters wide, in order to unite the forested strips of the two properties.

The farms of these peasants restore hope, because in hundreds of other hectares of this region of Caquetá, the traces of devastation are evident: burned trunks that are the testimony of a tragedy that is just now being understood. It is a cemetery of trees at which, from time to time, some wild animals arrive who still do not understand that this territory is no longer a home.

Reforesting takes time, and the change will not be seen in the blink of an eye. Merly Julieth Ducuara, from the El Recreo farm in the village of El Jordán, has been engaged in the project for less than a year, but has already planted 1,700 meters of live fences.

“Why reforest, Merly?”

“Because the effects of climate change are already being felt—the summer seasons are getting longer each time,” she replies, while Édgar Núñez teaches her how to prune a tree. “My husband and I are becoming obsessed with the trees.”

The field specialists and peasant farmers are convinced that if nature is given time, it will regenerate faster than anyone would expect. Baudilio Endo’s La Reforma farm is proof of that truth: his property has 53 hectares, and 22 of them are forested. In an area that used to be just pasture, today there are bushy trees, many planted by Endo and many others that have grown by natural regeneration. It has an agroforestry system with cacay trees, sugarcane, pineapple, banana and cassava. “I am going to plant 1,000 more meters with trees. My commitment is avoid cutting down the trees and to continue reforesting, even when the project ends,” he says.

When he walks around the farm, the temperature drops. The results of his efforts in these nearly four years are so evident that his neighbor, Eudilio Gómez, from the El Porvenir farm, has decided to follow in his footsteps. Through example, Endo has taught other farmers that the land can be worked in a different way and that the forest is necessary to ensure the continued existence of humanity.

The heart of the Bajo Caguán

A troop of monkeys were shaking the branches of the trees on which they were perched. Angrily, they threw sticks at Alexander Meneses, a peasant farmer who was below, cutting down the forest on his farm to turn it into a pasture. The mammals seemed enraged. Meneses says that when he looked at them, he felt sorry, but he thought that he could not do anything. He then decided to help them: he stopped logging and left the rest of the rainforest intact.

This occurred in 2019, and became one of the main reasons why Meneses decided to keep almost 40 of the 80 hectares forested on his Tres Quebradas farm in the village of El Jordán. “I used to say: we are damaging their home, we are displacing them, and they are vital in the ecosystem because they help transport the seeds,” he says, while drinking a glass of juice of the badea, a fruit typical of the region that he now cultivates on his farm.

One of his neighbors insists that he should cut down his remaining forest, but he doesn’t want his property to look like others, where the peasant farmers don’t even have firewood to cook. He took his promise to preserve the forest very seriously and a year ago, he joined the initiative of the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT). Now, he not only has stopped cutting down the rainforest, but also has turned his farm into the “cradle” of the trees that will be planted throughout the Bajo Caguán. In the last six months alone, more than 12,000 trees have been planted on the 36 farms, but the goal is to reach 58,000.

After learning that bringing the trees by boat from outside was not a very good idea, since they arrived damaged and not all of them survived, Meneses was chosen to build the project nursery together with Jhon Fredy Sabogal, an ACT leader who provides daily field support to the families. There are currently a little more than 25,000 trees in the nursery, including yopo (Anadenanthera peregrina), acacia (Acacia melanoxylon), Gliricidia sepium, mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), açaí, Ceiba pentandra, breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis), chontaduros, soursop (Annona muricata), cherimoya (Annona cherimola) and Pourouma cecropiifolia, among others.

What science tells us, the peasant farmers have learned empirically. “I have seen that when deforestation takes place, the cattle are beset by more diseases and parasites. Without trees, the cows have nowhere to find shade,” says Meneses. Not only that: he also says that along with the trees, the native bees are returning, the ones that help the plants bear fruit and ensure an abundance of food.

Daniel Villamil, a biologist and head of ACT’s program for the care and management of native bees in the Colombian Amazon, says that many of the peasants, who previously engaged in “honey hunting,” or the exploitation of bees, are now concerned for the bees’ conservation and care. Thanks to the joint work of ACT and Corpoamazonia (the environmental authority in this area of the Amazon), 45 families throughout Caquetá have been trained and certified as meliponiculturists (stingless bee keepers)—one of them in the Bajo Caguán. For them, this is a way to promote sustainable community development, strengthen food sovereignty, and increase the conservation of native forests and the restoration of degraded areas.

The dream of these peasant farmers is to become an inspiration for other families, potential leaders who are committed to taking care of the Amazon forest and reforesting the territories that were once deforested.

Other conservation initiatives

ACT is not the only organization working in the Bajo Caguán. The Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development (Fundación para la Conservación y el Desarrollo Sostenible, FCDS) is currently developing the Sustainable Livelihoods Program, which seeks to create other sustainable production options that generate income for communities in areas with active deforestation centers. Today, they are working on a community forest management initiative with two aims: the first is to cultivate both timber and non-timber trees, and the second is to work on sustainable production reconversion processes, through the creation of corridors that connect the forested patches. “Everyone is committed to conserving,” says Emilio Rodríguez, coordinator of the program, who points out that the 250 families that have been associated with the program have themselves chosen the type of project they will develop. Some opted for silvopastoral systems, some for agroforestry practices, and others have trained as beekeepers.

Additionally, the Amazon Institute for Scientific Research (SINCHI) is currently executing the GEF’s Heart of the Amazon project, which creates conditions for the conservation of forests in the area of influence of the Chiribiquete National Park.

One of the initiatives that resulted from this program was the construction of a plant to extract oil from the canangucha palm (Mauritia flexuosa) in the village of El Guamo, as well as in the municipality of Cartagena del Chairá. 69 families provide the product and sustainably use the 4,000 palm-producing hectares, which are located between the villages of Santo Domingo and Las Palmas. The idea, says Jaime Barrera, a SINCHI researcher, is to use the palm oil and, with the residue that remains, make concentrates for animal feed. They are currently developing a management plan in order to obtain permission from the environmental authority and be able to market the products.

The hope is that in a few years, when these agroforestry initiatives and systems begin to be the primary livelihood of hundreds of peasant farmers, deforestation will belong only to history, a history that no community will want to repeat.

Media Relations

For press release inquiries, please contact us at info@amazonteam.org.

Related Articles

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.