A Kogui sacred site

Many know the Kogui indigenous people of Colombia for their worldview: the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range, their ancestral territory, is revered by them as the heart of the world, and if it is not in balance ecologically and spiritually, then in the Koguis’ perception their world, our world, will lay in disarray. Less well known is that the coast surrounding the range is also part of their ancestral territory, and hosts many of their sacred sites, locations of worship and healing for the Kogui that also reinforce their connection to the sea.

Jaba Tañiwashkaka is a sacred site spanning 528 acres in the department of La Guajira. For the Kogui peoples, Jaba Tañiwashkaka is the origin of the natural world that forms their territory. It is one of 348 sacred sites across the Linea Negra, a ring of sacred sites surrounding the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta that is of immense cultural value to the Kogui, Arhuaco, Wiwa and Kankuamo peoples.

The Jerez, a river originating in the high points of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, flows into the sea at Jaba Tañiwashkaka’s eastern edge. Today, you can spot American crocodiles napping half-hidden in the mud of the Jerez River, and wary capybara grazing on the river’s banks. Ten years ago, Jaba Tañiwashkaka faced chronic pollution across its seashore, forest patches, mangrove swamps and riverbed, making these areas unhospitable for the special native ecosystems. Buffalo and cattle from nearby pasturelands trampled over the fragile roots of mangrove trees. Old mattresses, soggy cardboard boxes and all types of plastic waste from the town of Dibulla across the river were scattered across the beachside landscape, alongside abandoned fishing gear. Dry tropical forestlands surrounding the site were set aflame by local hunters seeking to trap wildlife. The Kogui felt disconnected from their sacred site, an important part of their ancestral territory that they began to lose during the colonial era and whose imbalance was deepened by current-day environmental degradation.

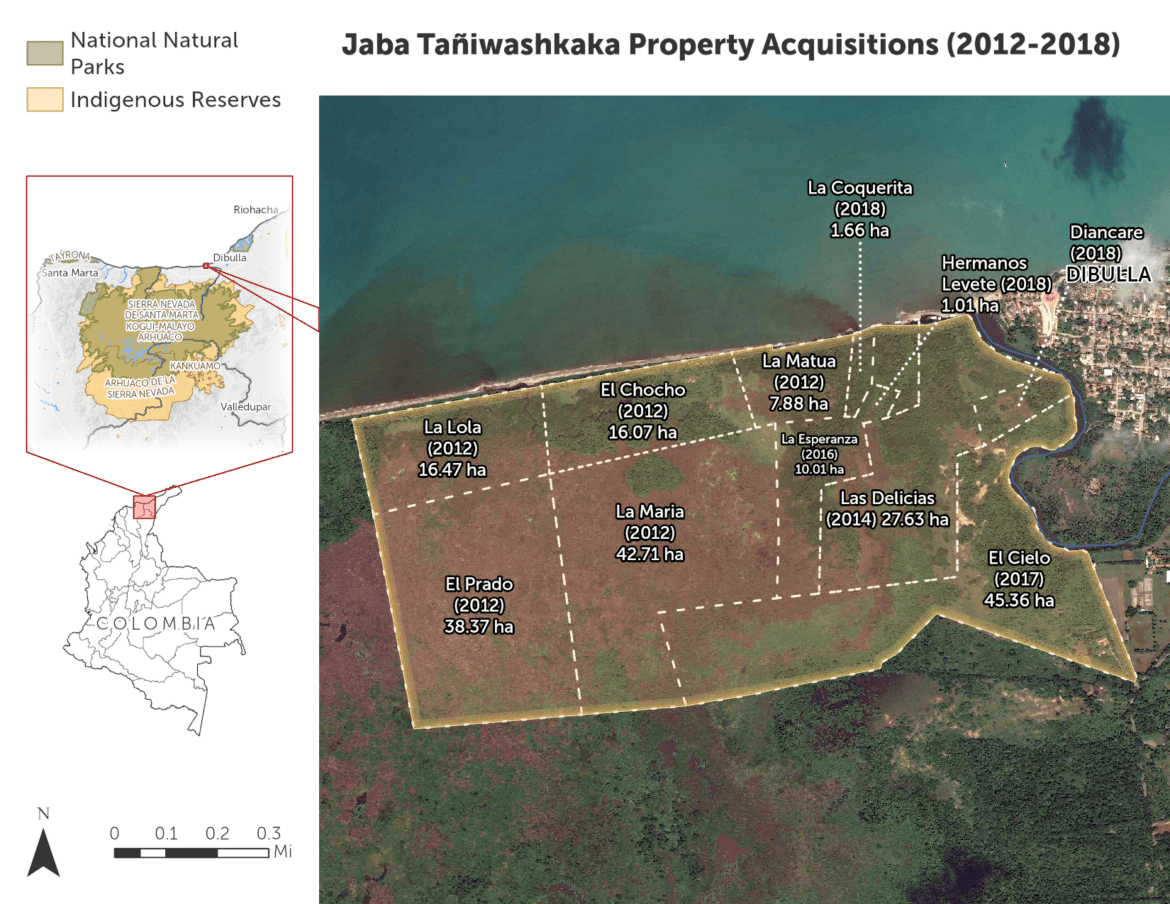

The Amazon Conservation Team has been active at the Jaba Tañiwashkaka sacred site for over a decade, assisting the legal titling of the land between the Kogui community and government stakeholders, integrating it as an indigenous reserve, purchasing private plots of land remaining on the sacred site, and assisting long-term governance activities lead by the Kogui, including territorial monitoring and the construction of culturally important infrastructure

Connections across the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta

Today, the land comprising Jaba Tañiwashkaka benefits from three different forms of legal protection, each of which strengthened the degree of autonomy and safety of the Kogui, ensuring the stewardship of the land in accordance with their cultural practice and livelihood. In 2012, the site was endowed with protection by Colombia’s Ministry of Culture as an area of national cultural interest, making it the first time this designation was assigned to an indigenous sacred site in Colombia. In 2018, a presidential decree defined and recognized Jaba Tañiwashkaka as a sacred site along with 347 other sacred sites connected to and part of the Linea Negra complex, the ancestral lands of the Kogui, Arhuaco, Wiwa and Kankuamo peoples, establishing special cultural and environmental protection privileges. Finally, in 2021, through a decision of the National Land Agency’s board of directors, the sacred site was formally integrated into the Kogui-Malayo-Arhuaco indigenous reserve, granting stringent protection against territorial incursions and other disturbances.

Ebawi Zarabata Pinto, a young Kogui community member, speaks to the importance of Jaba Tañiwashkaka’s inclusion in the reserve:

“It is very important that Jaba Tañiwashkaka is now within the indigenous reserve. That is a strength for the mamos [traditional Kogui authorities] in the Sierra, that they can descend and collect their materials for different types of spiritual work. That is very important. Not just for us, but for the animals and everything above us.”

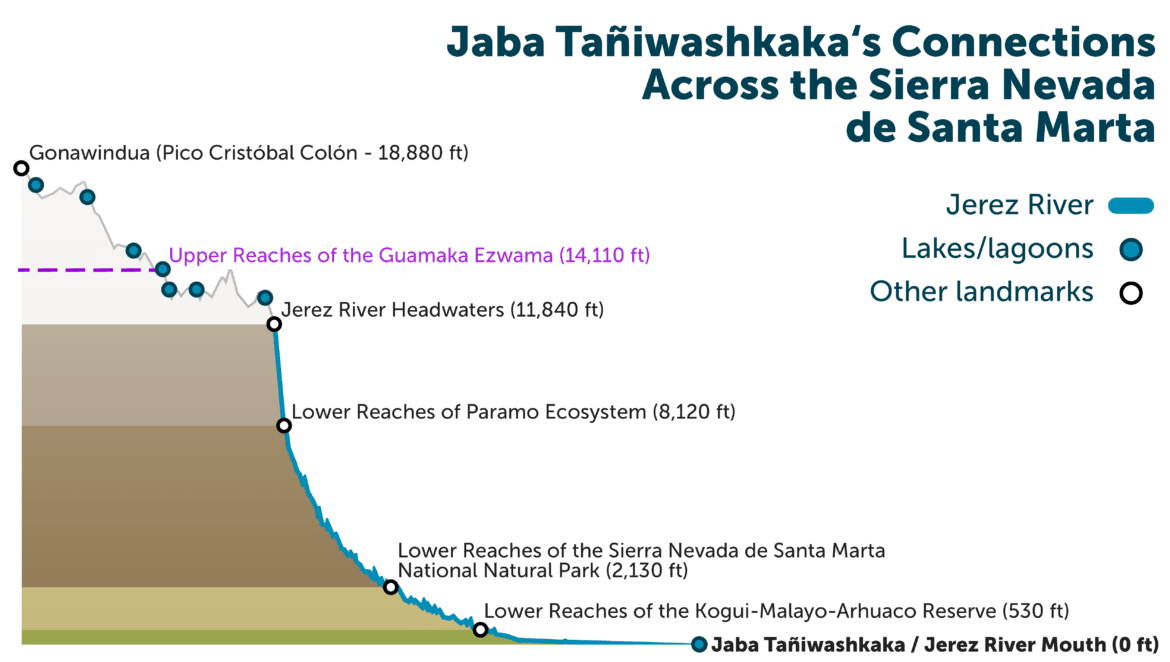

Mama Shibulata, a Mamo or traditional authority of the Kogui, stresses the intricate hydrological connections between the sea and the mountaintops of the range. He says that the water that is born in the marshland lagoons on Jaba Tañiwashkaka is the same water that is found in the high-altitude lagoons, called the Ezwamas, of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, at 11,000 feet. He continues that by making spiritual offerings to the water in the sea-level lagoons, one feeds those prayers upstream to the lagoons on the mountaintops, and if one does this at the top of the mountains, the offerings are fed downstream into the river’s mouth at the sea. The local indigenous groups believe that these prayers ensure the ecological integrity of the region.

Sacro-ecological restoration

The Mamos understand each component of nature as having a function and order to which spiritual offerings are made. The Mamos thus manage the territory in accordance with authorities they identify in the natural world such as headwaters, coastal lagoons, marshlands, and trees. Exemplifying this practice, the area of Jaba Tañiwashkaka was left alone for some time to allow it to spiritually heal and to provide it with the conditions to initiate its natural regeneration.

“Through the legal expansion, that territory now belongs to us. It belongs to the community. This is very important, because now we can be present in this place; we can be at peace.”

– José María Conchacla Mojica, Kogui community member

During the site restoration process, the strength of traditional cultural practices was essential, including the physical labor of clearing trash from the mangroves, beach and river, and fencing the sacred site so cattle and buffalo could not trample the fragile ecosystems. Through the cultural infrastructure we helped build, traditional ceremonies were held once again at the sea, reviving centuries-old traditions. Some members of the Kogui community began to live on the site, sowing traditional food gardens and monitoring the territory for threats. The Kogui assigned paramount importance to their offerings to nature in the process of reviving the site’s life force.

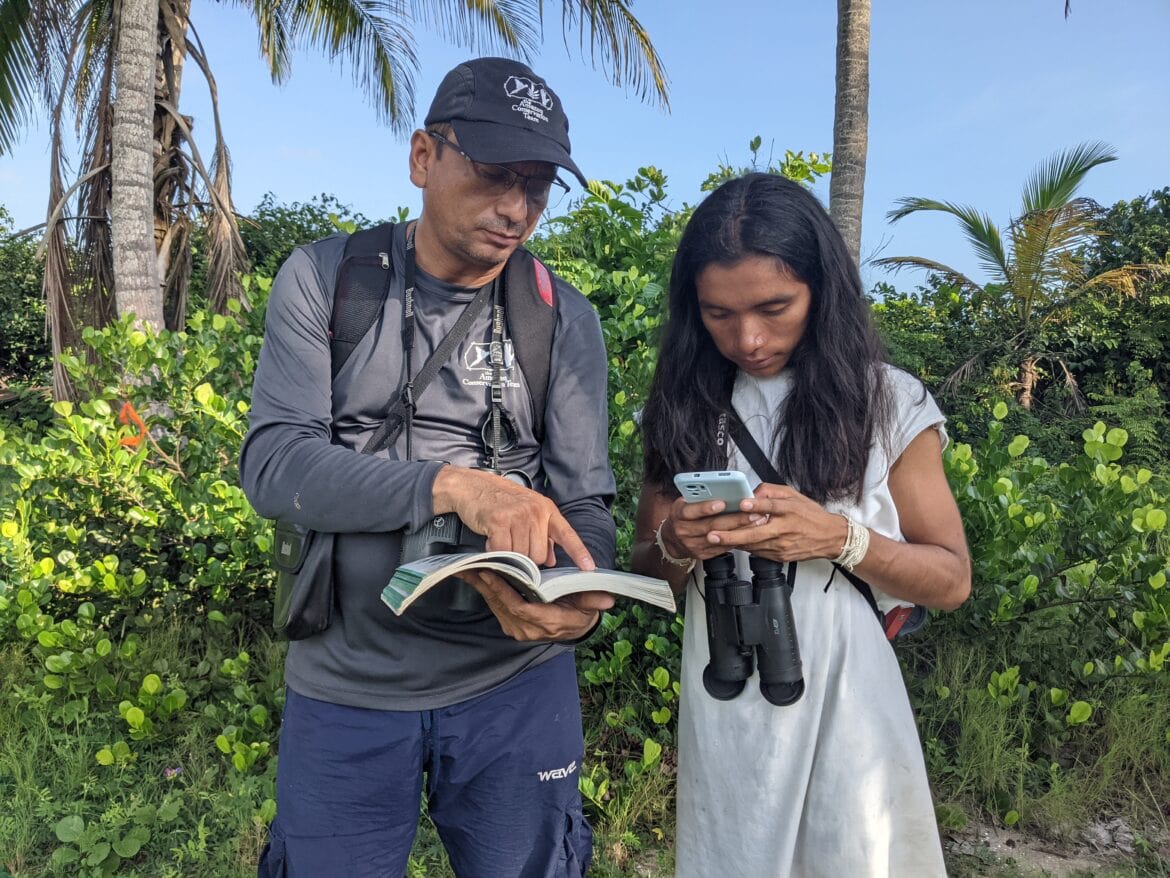

The current phase of this decade-long ecological restoration process is facilitated by the Koguis’ traditional territorial management activities. These activities include spiritual offerings by Mamos seeking to manage the spiritual energies of the watershed, the documentation of indigenous names for and oral histories about species to serve as a knowledge base for future generations, and the use of traditional locations as biodiversity monitoring points. Western scientific practices such as assigning species names and the use of data collection applications including ARCGIS’s Survey 123 complement this process, facilitating communications regarding the project to non-indigenous partners.

An intercultural ecological monitoring team made up of three Kogui community members and three ACT staff members supports a long-term joint conservation effort between our team and the Kogui community. They have been documenting the presence of wildlife, habitat growth, water levels, and disturbance events, generating primarily positive news regarding the site’s resurging ecological integrity.

During a yearlong monitoring session from September 2021 to October 2022, the team recorded the presence of 40 out of the 42 listed bird species that serve as indicators of ecological health in the region, averaging 29 of these species observed year-round. This signified a major uptick of native fauna for an area that previously was nearly devoid of diverse wildlife. Because Jaba Tañiwashkaka is a wetland, many migratory bird species from North America use the site as a sanctuary to rest before heading further south. Through our joint monitoring efforts on the site, 51 migratory species have been identified and more than 225 unique bird species have been recorded.

Jaguarundis, crab-eating foxes, ocelots, collared anteaters, capybaras, and spectacled caimans are among the species indicating ecological health observed on the site. Across the monitoring year, the team recorded the presence of 15 out of 22 of these animal species. Many of these animals were observed in mangrove or beach habitats, some of the most degraded locations prior to the Koguis’ official stewardship in 2011.

Juana Londoño, coordinator of our Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta program, observes that the restoration effort’s benefits go beyond the sacred site: during the fall months, when it is lobster and shrimp season along the coast, local fisherfolk know that thanks to the Koguis’ restoration and stewardship of Jaba Tañiwashkaka, the catch is much better in the sea directly surrounding the sacred site. “If this site had tourism infrastructure and lights, the catch would suffer,” Juana notes.

The resurgence of life at Jaba Tañiwashkaka today came about only through the enormous dedication and strong will of the combined team, who tirelessly worked to ensure Jaba Tañiwashkaka was formally recognized and protected for its biocultural value to Colombia and the region. Kogui community member José María Conchacla Mojica describes the importance of the most recent legal protection assigned to the site in 2021:

“For us, the territory is a unity. It is like a house. Everything is there: the culture, and the knowledge. But legally, this did not belong to the indigenous people. Through the legal expansion, that territory now belongs to us. It belongs to the community. This is very important, because now we can be present in this place; we can be at peace.”

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.