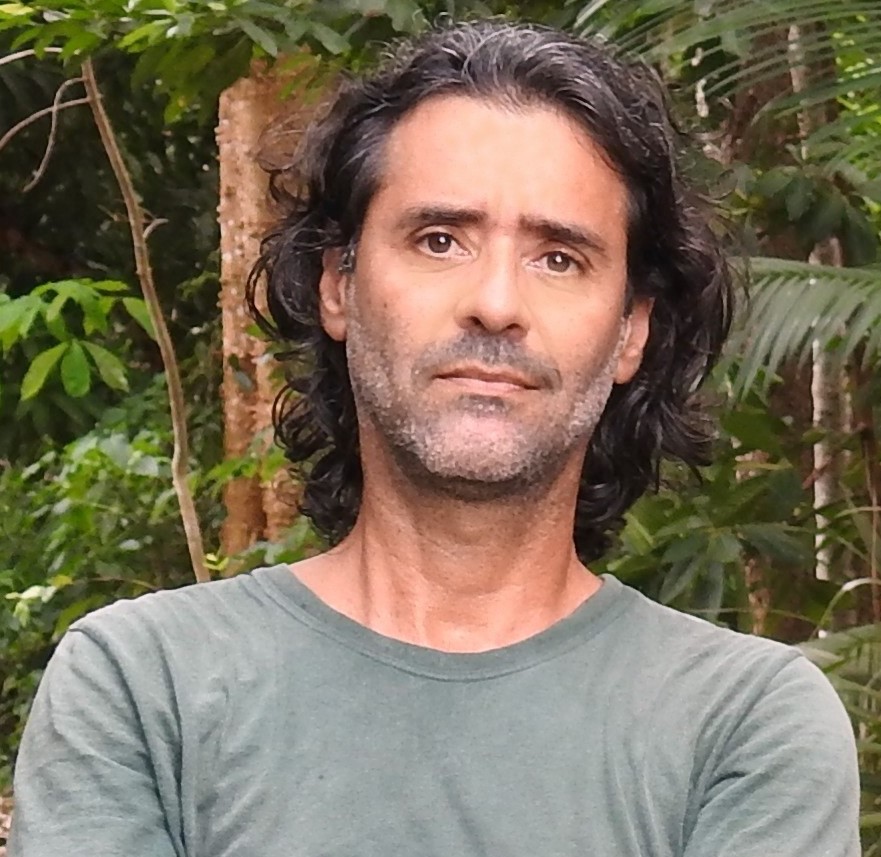

We sat down with ACT’s Evandro Bernardi for a firsthand look at how indigenous communties in the Brazilian Amazon are being impacted by the virus, and how ACT-Brasil is helping them respond to this crisis. Evandro has worked with indigenous communities for more than 20 years, and coordinates ACT’s fieldwork in the northeastern region of the Brazilian Amazon.

Q: Overall, what is the situation like for indigenous communities in the Brazilian Amazon?

The latest numbers (as of August 24) show more than 20,500 people have contracted the virus across 126 tribes, and 599 people have died. But there is lots of underreporting. There are villages that have unreliable communication systems, or where health services do not come at all or come with few resources. We are 99% certain that there are many, many more cases and deaths than have been reported.

Here in the northeastern Amazon, the most impacted villages are in the northeastern-most areas along the border with French Guiana. It’s accessible by road, so you have many people circulating, entering and exiting the indigenous territory. Our partner communities in the Tumucumaque Indigenous Park and Rio Paru d’Este Indigenous Territory are accessible only by plane. There are no roads, and at some points even the rivers are not even navigable. Even so, practically all villages have cases.

Q: In these extremely remote regions of the rainforest, how could the virus be spreading?

Before the first reported surge in cases, people had already been returning to their villages. They could have brought the virus in. In other places, like our partner village of Missão Tiriyó, there is an established military presence with a constant flux of groups—one battalion leaves, and another comes in to replace them. These people could be carriers, and so could the illegal miners or health teams moving in and out of areas as they do in the Amazon. Even though boat travel has been restricted across the Amazon, there has been a surge in clandestine travel along the smaller rivers and under the cover of night. The rivers are like arteries for the spread of the virus.

Q: What are the most pressing and urgent needs of impacted communities right now, and how are you and the ACT-Brasil team helping to respond?

Food, professional health support, and preventive resources like masks and sanitizers are critical. For villages accessible by road, these can all be delivered relatively easily. In the case of our partner villages only accessible by plane, it’s more complicated. We have contact with the army for this, which is complicated too. For example, a group of soldiers were stranded at their battalion near Missão Tiriyó, unable to leave because the military flight to come collect them had technical problems. They ended up taking a flight chartered by ACT-Brasil, actually the return leg of a flight we organized to take people back to their home village of Missão after being stranded in the city of Macapá. Air freight is very expensive too, so you spend a lot on a flight that might not even be able to take all of the supplies a village needs at one time.

But we’ve been able to distribute a large number of resources and health safety materials to communities, more than 600 masks, and over 470 cestas basicas (standardized packages of essential food supplies). The indigenous peoples that returned to their villages took food supplies with them for their period of quarantine, and we also provided hygiene and cleaning materials for disinfection. We’ve also sent some tools they need to be self-sufficient in the rainforest, like hooks and fishing lines.

In addition to the authorized charter flights we arrange, we collaborate with FUNAI (the national agency for indigenous peoples), the military, and health services to take foods and health safety materials on their trips to villages. It requires a large network of support to be able to get all of these materials to the villages.

Q: One of your response activities is helping indigenous people stranded in the city get back to their home villages. What has that process been like?

At the end of July, we scheduled and coordinated logistics for return flights for some indigenous people that are here in the city of Macapá (the capital of the Amazonian state of Amapá). 39 people went back to two villages in the western portion of the Tumucumaque Indigenous Park—Puxaré at the headwaters of the Marapí River, and Missão Tiriyó at the headwaters of the Paru River. Back in their villages, they will quarantine with the support of a local health team from the DSEI of Amapá and northern Pará. This team is actually comprised of indigenous peoples who are trained as healthcare technicians. Afterwards, the health team will evaluate these community members and release them from quarantine.

Q: Can you speak more to the role of civil society in addressing the crisis in Brazil?

We are living in a very difficult political situation in Brazil in this current government, with measures that are totally anti-indigenous. It has gone as far as not even giving support in this time of emergency to indigenous peoples. In July, the congress and senate passed a bill for an emergency plan with support including water purifiers, medicine, and protective equipment. When it arrived on the desk of the federal government, the president vetoed several of items of this project specifically for indigenous peoples—22 measures were vetoed. Out of all of the bills during this government so far, this one had the most vetoes.

In this situation, it is really NGOs and civil society organizations that we can say are on the frontlines of the fight against Covid-19. For example, in Tumucumaque and Rio Paru d’Este, small primary care units known as UAPIs (Unidades de Atenção Primária Indígena), were set up through the efforts of partner organizations because the federal government and those responsible for health did not have the resources to do so.

Q: How can we best support indigenous communities through this, and what does it look like afterwards?

The soul of our organization, and organizations like us, is to support indigenous communities and their representative organizations in the way they need. And today, it is humanitarian support so that these communities can suffer the least impact in this moment.

And then after this, we continue our partnerships based on their requests, discussing what they want and need to reach a better future. From there, we support them in initiatives so they can live the fullest lives possible on their lands with what they want and need, like plenty of fishing and hunting, a standing rainforest, abundant cultivation plots, and happy and joyful children bathing in the clean river. And that’s it, at the end of the day, that’s our work and what we love doing.

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.