Amazon fires jeopardize indigenous tribes living without contact with the world

Article originally published in Revista Semana, September 18, 2019

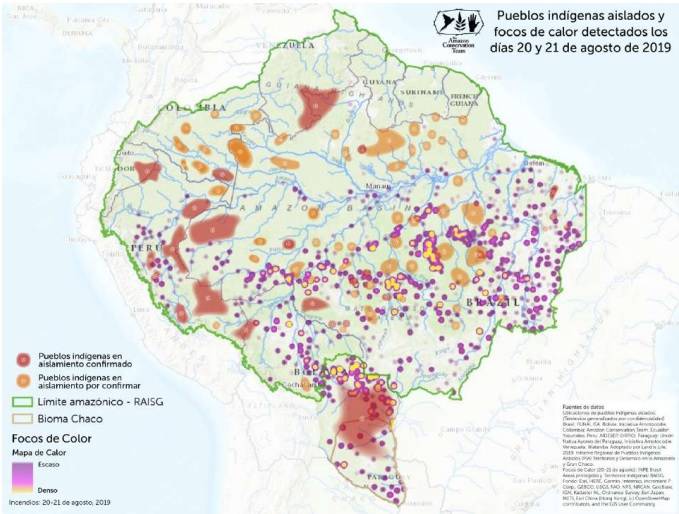

Seventeen organizations called on the governments of the Amazon countries to stop the environmental debacle and protect the indigenous people in isolation. Nearly 70 uncontacted indigenous groups have already been confirmed in the Amazon, two of these in Colombia: the Yuris and Passés.

Faced with the worst-case scenario that the Amazon is experiencing—the irreparable loss of forests due to forest fires—17 organizations in the region denounced the dramatic situation suffered by Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact (PIACI), hidden inhabitants of the rainforest. In the region, there are records of 185 possible isolated communities, of which about 70 have already been confirmed.

“These peoples are under constant threat. The current fires greatly aggravate their situation and are a risk to their physical integrity. The results of a predatory development model, together with the negligence of the State in protecting the isolated groups, increase the socio-epidemiological vulnerability to which they are subject,” states the document signed by indigenous organizations from seven countries: Colombia (the Amazon Conservation Team Colombia, and the National Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the Colombian Amazon), Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela and Paraguay.

The organizations said that the institutional dimension, related to the development policies of the region, is associated with autonomous and illegal initiatives that constitute vectors that increase the risk of loss of life for these populations. “This is the reason why it is necessary for governments to give special attention to peoples in isolation and in initial contact.”

In the rainforest territories, some 350 indigenous groups live and depend on the tropical forest, as well as hidden indigenous groups that have remained without contact with civilization since the time of the conquest. They decided to flee from the diseases and harassment of the Spaniards and Portuguese in order to camouflage themselves within the deepest parts of the rainforest.

Threats such as deforestation, fires, illegal structures and new agro-industrial developments force isolated indigenous groups to develop survival strategies, such as involuntary displacement, “compelling them to seek refuge in regions that do not correspond to their traditional territories. This forced migration puts them in imminent contact and even confrontation with people outside their group. ”

The 17 organizations demand that the governments of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela and Paraguay (the latter affected by fires in the Gran Chaco area) to take immediate measures to counteract the fires and other threats, in addition to implementing special

protection measures that respect the self-determination of these indigenous groups to remain in isolation.

The authors of the document decry that behind the burning of the Amazon, and areas such as La Chiquitanía in Bolivia and the Gran Chaco, there is a billionaire market. “In Brazil, setting fire to an area of 1,000 hectares costs around one million reais on the black market. Who pays that amount, and what do they earn? The countries of the Amazon basin and the Gran Chaco must ensure the protection of the 185 communities that potentially live in this region.”

Brazilian disinterest

The regional statement for the protection of isolated indigenous groups, prepared by the 17 organizations, also explored the relationship between forest fires and uncontacted indigenous groups in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela and Paraguay.

With respect to Brazil, the text emphasizes the lack of interest of the Brazilian government in the indigenous population and environmental issues. “For months, President Jair Bolsonaro delivered speeches against the indigenous peoples and the environmental movement. He has been disrespectful with regard to environmental legislation, and his pronouncements before organized civil society are argumentative and express contempt,” the joint statement declares.

According to the document, this year, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has increased by 278 percent relative to the same period in the previous year. “Between August 15 and 20 of this year, 131 indigenous lands experienced fires, a number that is increasing rapidly. This chaos increases the dramatic situation of two indigenous peoples in isolation. These figures were drawn from official data of Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE).”

In Brazil, there are 114 records of possible indigenous peoples in isolation, of which 28 are confirmed by the official governmental indigenous affairs agency. “How many of these are fleeing the fires? The information collected suggests that 15 fires are in lands where there are records of isolated indigenous groups, especially in the states of Mato Grosso, Pará, Tocantins and Rondônia”.

Peru, land of isolated peoples

A map prepared by the Amazon Conservation Team shows that Peru is one of the countries with the largest presence of isolated indigenous peoples (although the document does not reveal their total number), indigenous groups that are located in of international border areas, especially along the border with Brazil.

“There has been a proliferation of intense fires. That is why it is necessary to consider that the possible progression of these wildfire fronts towards the west in certain sectors could entail serious risks to the isolated peoples and their territories in Peru”, the organizations note.

The mountainous areas, including Cusco and Ayacucho, are the most recently affected by forest fires in Peru. However, the document indicates that some fires occurred in the dense rainforest, in areas directly linked to isolated peoples. “This has a serious impact, both in the conditions

of the territory and in the quality of the air and the natural resources the isolated peoples need for their livelihood, thus affecting their rights to life, health and food security.”

One of these forest fires occurred in the area proposed for the creation of the Sierra del Divisor Indigenous Reserve in the province of Ucayali, which is part of the department of Loreto. “In this area, which is connected to the Sierra de Divisor National Park and the Isconahua Indigenous Reserve, there is already official recognition of isolated communities.”

In the district of Iñapari (department of Madre de Dios), near the Alto Purús National Park, another significant fire was recorded, which undoubtedly affected the isolated groups. “It is one of the areas with the greatest displacement of isolated groups, known by indigenous organizations as the Pano-Arawak cross-border territorial corridor, between Peru and Brazil. The concern is compounded by the lack of prevention for this type of emergency, especially given that in Peru, one of the main territorial threats is the increase in deforestation and illegal activities,” states the manifesto.

And Colombia?

The recent environmental debacle in South America did not touch the Amazon rainforests of the Colombian territory, covering more than 53 million hectares. This does not mean that it is a territory free of fires or deforesters; rather, the reason is linked to climate.

In the Colombian Amazon, the dry season has its highest peak between December and March. According to the Environmental Information System of the Sinchi Institute, between 2018 and 2019, the region presented more than 25,000 reports of fires, reaching its highest peak in February, with 16,400. In August and September, there is still rainfall, which is why the fires are currently few.

But deforestation does affect the region almost daily. The 17 organizations said that between 2016 and 2018, the Colombian Amazon lost 478,000 hectares of forest, of which 348,000 hectares were primary forest, with serious repercussions for the corridor between the Andes, the Amazon and the Orinoquia.

“So far in 2019, alerts indicate an additional loss of 60,600 hectares, of which 75 percent was primary forest. This deforestation primarily impacts four protected areas: the Tinigua, Sierra de la Macarena, Nukak National Reserve and Serranía de Chiribiquete national parks, which may be home to indigenous peoples in isolation”.

In the vast Colombian Amazon rainforest, the existence of two isolated indigenous tribes, the Yuri and Passés, which live in a part of the Rio Puré National Park, located in the department of Amazonas, has already been confirmed. However, there are strong indications of 18 more communities.

The biggest concern is in Chiribiquete, a national park that has lost 2,600 hectares of forest since its expansion in July 2018. Of the 18 indications of isolated communities in Colombia, two of them are in this protected area, “the Carijona and Murui, still to be confirmed,” per the document.

Daniel Aristizábal, coordinator of the Amazonian plains and isolated peoples team for the Amazon Conservation Team Colombia (ACT), agrees that deforestation is the major problematic in areas like Chiribiquete.

“Behind this action is unbridled capitalism that has no connection to the ecosystems. The western human being has the conception of experiencing and exploiting every place he knows about. He feels an obsession to explore, experience, record and report, without applying the precautionary principle, which constitutes a risk to the isolated peoples of the Amazon. We must get it into our heads that it is best not to go to certain places,” said the expert.

The Yuri and Passé, the two indigenous groups already confirmed in Puré, are not directly threatened by fires. The organizations defending the isolated groups argue that the groups are pressured by other factors such as the exploitation and exploration of hydrocarbons, the advance of the agricultural frontier, the development of road infrastructure, and mining.

“For two years, we have identified several drug trafficking routes through Puré. On the Putumayo and Caquetá rivers, there are military bases in Colombia and Brazil, so the narcotraffickers, in order to avoid passing by these installations, are instead shifting down the Puré River. Although the isolated groups live at a distance from that route, at any time contact might occur, which would unleash a confrontation between both sides. There is also a strong threat from selective wood extraction in the southern part of the Park,” says Aristizábal.

Diana Castellanos, territorial director of the Amazon directorate of the National Parks System, reported that in 2012, after confirming that the Yuri and Passé were in Puré, the entity created a management plan to specify the location of intangible areas where no one can carry out activities that affect these groups. “Next, we began discussions with the Ministry of the Interior to move towards a public policy on indigenous peoples in isolation, which was established through Decree 1232 of 2018.”

With respect to Chiribiquete, Castellanos believes that there are strong indications of the presence of isolated groups in the southern part. “We work with neighboring reserves like Mirití. These indigenous people confirm the presence of the isolated groups and have internal rules so as not to disturb them. Today, we are updating the management plan to include areas in the northern part, which have overlap with lands occupied by settlers, and in the south we built a guard post to prevent the entry of foreigners to the area.”

Multiple Ecuadorian threats

Like Colombia, Ecuador has not recorded recent fires in its Amazon region. However, it suffers from other types of illegal and legal activities just as harmful to biodiversity and its indigenous peoples.

The statement reports that mining is moving into indigenous territories in the southern part of the Ecuadorian Amazon, causing a huge loss of biodiversity, water pollution, and the displacement of the Shuar community. For its part, the northern part has been damaged and contaminated by oil activities for decades, and currently suffers from dramatic episodes of increased rainfall.

Other threats detected in the rainforests of Ecuador are the advance of the agricultural frontier and the development projects promoted by local governments, such as the building of new roads that encourage colonization and the displacement of indigenous communities such as the Waorani and Kichwa.

“The Yasuni National Park, where the Tagaeiri and Taromenane indigenous groups live in isolation, is now free of fires. But deforestation derived from the exploitation of oil by new roads and platforms puts the survival of these groups at serious risk,” says the document.

Mining, an executioner in Venezuela

The Venezuelan Amazon region covers more than 45 million hectares, where more than 25 different indigenous peoples are present. To date, there are three confirmed indigenous groups in voluntary isolation: the Uoti, Uwottuja and Yanomami, located in the rainforests of the states of Amazonas and Bolívar.

There are no recent reports of fires in the areas inhabited by isolated communities, which does not indicate that they live in total tranquility. The signatory organizations decry that illegal mining activities are carried out in the two states, where armed groups guard the mining camps and threaten the indigenous members who denounce the problems.

In the state of Amazonas, there are approximately 6,000 miners carrying out gold and coltan mining, the document of the 17 organizations reports. “This situation affects the groups in isolation, since these activities occur in the areas close to their habitat, impacting their chances of physical and cultural subsistence,” the analysis concludes.

The Wataniba Association and the Regional Organization of Indigenous Peoples of Amazonas (ORPIA) are working to build awareness of the situation so that the Venezuelan state will establish protection policies with respect to these isolated groups and their territories.

Bolivia and Paraguay

So far in 2019, more than one million hectares of forest have been burned in Bolivia, the analysis reports. This hecatomb had its peak between July and August, when more than 780,000 hectares of the Chiquitanía region were affected by forest fires. Ayoreo, Chiquitano and Monkoxi also felt considerable impacts.

“Many dry forests on the border with Paraguay have disappeared, a region decreed with intangibility for the isolated peoples of Ayoreo and the Guaraní territory. These areas represent the last refuges for their survival, areas that are increasingly threatened by agribusiness and the government itself,” the organizations charge.

Although it is not an Amazonian territory, these organizations decided to include Paraguay in their analysis due to the environmental impacts unleashed by the production model imposed by agribusiness, which they categorize as primarily responsible for the large fires that have consumed the natural forests of Chaco, the second largest in forest area and coverage in South America after the Amazon.

“The use of a burn management system that was applied to natural environments in the past, at that time limited and with a minor destructive impact, today represents one of the greatest threats to life. A million hectares of forests have recently disappeared, vital areas for the indigenous people in isolation in Ayoreo.”

The Chaco natural reserves represent the few refuges that are left to the Ayoreo isolated groups. “The other forests have been consumed to provide for livestock and exploitation of natural resources. The absence of the Paraguayan state in the control of its reserves and in the protection of the life of the isolated peoples are proof of their disinterest in the conservation and protection of their heritage.

What we lose daily

The Amazon, the largest hotbed of biodiversity on the planet, is covered by a black halo of devastation. Deforestation, a macabre activity that uses chainsaws to knock down trees and fires to burn away all traces of life, continues to transform the dense forest into an arid flatland ready to receive livestock, illicit crops, roads, homes and agribusiness.

This year, the planet witnessed the true face of destruction in the Amazon, a region made up of more than 670 million hectares of forest distributed in nine South American countries. The Brazilian rainforests were the greatest victims, places where chilling images were captured of burned vegetation, voracious and uncontrolled flames, dead animals, severed trees and indigenous people cornered by fire.

According to INPE, between January and August 2019, more than 80,000 fires burned in the Amazon rainforests of Brazil, a figure that represents an increase of 80 percent compared to the same period of 2018. According to the entity, the month of August was the most fateful, with the most extensive, intense and persistent fires.

Reports from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) confirm that hypothesis: the Brazilian Amazon lost more than 2.4 million forested hectares due to the fires (an area four times larger than that recorded in 2018). Meanwhile, in 2019, the loss of forest associated with fires across the entire Amazon region already exceeds 4.3 million hectares, an increase of 150 percent compared to last year.

Faced with this green catastrophe, the world shuddered and began to pray for the Amazon in social networks (#PrayforAmazonia was the selected hashtag), while environmentalists raised their voices to emphasize that to attack the region is to put the life of the planet at risk: it is a region that functions as the heart of the world.

Per the WWF, the Amazon rainforest, the largest in the world, daily releases water that rises into the atmosphere through evapotranspiration, and then flows through the air to various parts of the Americas in the form of “flying rivers.” In other words, rivers, wetlands and other bodies of water in other parts of the continent depend on the presence of these wooded areas, which contain between 90,000 and 140,000 million tons of carbon.

The Amazon’s dense rainforest is home to 10 percent of the biodiversity known so far on earth, represented in 427 species of mammals, 40,000 plants, 1,300 birds, 378 reptiles, 400 amphibians and 3,000 freshwater fish.

Media Relations

For press release inquiries, please contact us at info@amazonteam.org.

Related Articles

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.