El Espectador / December 17, 2021

In Putumayo, five SISPIs (Indigenous Intercultural Healthcare Systems) are being developed with indigenous communities. This project generates healthcare models that respond to the needs of the communities themselves; however, the process of dialogue with the institutions can be complex.

Through December 16, 2021, 2,109 indigenous people had died in Colombia from COVID-19, and the sum of active cases had reached 72,435, of which 2,123 correspond to the Putumayo department. This scenario is partly due to the fact that in departments such as Amazonas, Putumayo, Caquetá, Guainía, Guaviare and Vaupés, it is difficult to reach healthcare centers due to geographical distance as well as the lack of physical infrastructure, technological means and qualified personnel to address the emergency. For this reason, in June 2020, indigenous communities issued litigation proceedings #0159, through which they demanded action plans to counteract the COVID-19 outbreak in the region. Today, as a result of this request, in Putumayo, healthcare models have begun to be developed that specifically respond to the needs of the communities.

Among the 15 indigenous peoples that exist in Putumayo, the Coreguaje, the Embera, the Murui, the Pastos and the Siona joined the creation of five SISPIs (Indigenous Intercultural Healthcare Systems), a model that not only seeks to address COVID-19, but also to structure healthcare systems based on a dialogue between indigenous knowledge and the epistemology of Western healthcare. These five communities were initially singled out due to the clarity of their self-designed community life plans. However, the indigenous facilitators who lead the project believe that all Putumayo communities can develop their own systems.

The reason for creating five different systems is that each community has its own medical foundations and practices, its own conceptions of health and disease, and a particular history within its territory. Through the SISPIs, it is hoped that the Putumayo healthcare centers will care for the indigenous population under their own criteria, thus avoiding the problems that the invisibility of this knowledge has generated among indigenous peoples who do not feel comfortable with Western healthcare concepts and thus do not access healthcare centers. The creation of these SISPIs entails three phases: first, the conducting of social characterizations of the healthcare in the communities; second, the development of action plans based on these characterizations; and third, consensus on said plans.

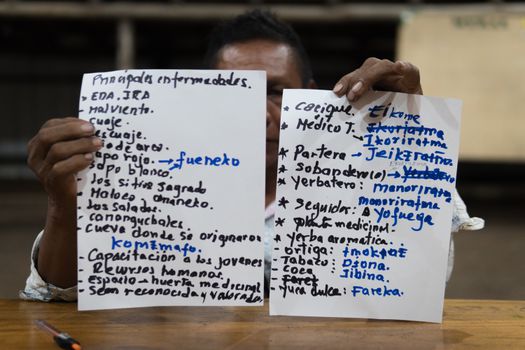

The first phase was carried out between March and the beginning of December of this year, with a methodological guide developed in conjunction with the Putumayo Health Secretariat and the NGO the Amazon Conservation Team, which establishes the non-exclusion of either ancestral medicines or Western medicine, instead generating a dialogue between these systems. The indigenous facilitators in charge of the process traveled, conducting surveys among the community members themselves and interviewing those with knowledge of ancestral practices. The objective was to observe the dynamics of the communities and their environmental, social and healthcare situations—such as their own and Western diseases within these communities—in order to develop an “x-ray” of the territory so that in the following phases, consensus could be reached on a public health-based system, given that their ancestral medicinal systems incorporate spirituality and territorial conservation, in many cases impacted by extractive projects and demographic growth. The locations for the surveys were georeferenced, given that members of the same ethnic groups are dispersed across the different regions of Putumayo.

During this phase, the elders also stated how they arrived at their knowledge. “This can strengthen the new generations and the exchange of knowledge—the spiritual dimension or the knowledge of medicinal plants, this is the exchange that takes place through this process,” says Victor Quenama, a member of the Cofan people and a support staff member of the Departmental Health Secretariat, who has served as the liaison between the institution and the Emberá people.

For Nelcy Timaran, who is also a support staff member of the Secretariat, the process is complex because each community has a different vision of health. She emphasizes that within the Secretariat, “the need for a differential approach and the message itself has been reaching the municipal health secretariats”, which intervene directly in the communities.

Paula Galeano, a member of the NGO the Amazon Conservation Team, states that “one of the most complex elements is the political dimension of the relationship between indigenous peoples and healthcare institutions, because there is a lot of knowledge lacking on both sides, and there is a need for relationship-building between these two universes”. She appreciates ??the willingness of the government to support these processes.

“Interculturality” entails the integration and creation of diverse visions around, in this case, health. The interviews and transcripts with the elders generate a record of ancestral knowledge that previously had been transmitted only orally. In the case of traditional knowledge-keepers who speak only an indigenous language, translation becomes part of the process, especially when there are terms that cannot be translated and equivalents must be created in Spanish.

The consensus-building objective of the SISPIs is scheduled for August of next year, and may serve as a model for other departments in the country. But William Yaiguaje, health coordinator for the Siona people, faults the Putumayo Health Secretariat, saying that “we have not seen support directly from the departmental secretariat. I hope that for the next phases, such support will be integrated, because the secretariat has this capacity. We are undergoing a learning process, and we call on the Ministry of Health and other partners to help us strengthen this process in which we apply our own knowledge.”

*This article is published through an alliance between El Espectador and InfoAmazonia, with the support of the Amazon Conservation Team.

Media Relations

For press release inquiries, please contact us at info@amazonteam.org.

Related Articles

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.