Located between the Caquetá (Japura) and Putumayo (Icá) Rivers, the Puré River (Purué in Brazil) is adjacent to the Colombian and Brazilian border. Since the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, there were rumors from rubber and animal skin traders about the presence of peoples who took shelter deep in the adjoining forests. The malocas (longhouses) of an isolated community were found in the headwaters area of this river, which is characterized by forested and undulating hills and surrounded by wetlands associated with the majestic canangucho or aguaje (Mauritia flexuosa) palm.

These are peoples who avoid all forms of contact with the surrounding society. Their neighbors—the Murui-Muina, Bora, Miraña, Yucuna, Cubeo, Matapi, Carijona, and Tikuna peoples—all share a similar story: these were victims of slavery who arrived upstream with the Spaniards and downstream with the Portuguese, and subsequently were victims of the genocide by rubber trade slave owners between 1879 and 1912. It is estimated that this resulted in 50,000 deaths in the region.

All these peoples, through their tradition and “Law of Origin”, respect and value their neighbors’ decision. They know the reasons behind their isolation.

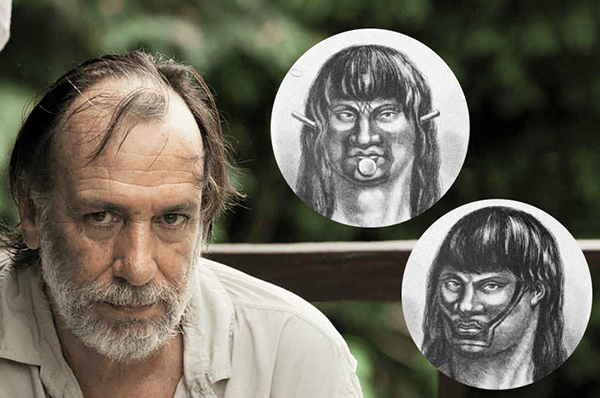

As occurs with many Amazonian peoples, the demonym associated with the isolated peoples is a situational issue and a matter of debate. Recent anthropological and linguistic research, together with conversations with traditional indigenous authorities, have resulted in their being referred to as the Yuri and Passe peoples.

According to indigenous ancestral knowledge, the Yuri and Passe are recognized as natives of these forests, but only in 1969 did the Colombian government receive the first notifications regarding their existence. In that year, a skins trader and former military official tried to make contact with these peoples in order to get them to join his crew of exploited workers, making his way between the Caquetá and Putumayo rivers. He never returned. Without context, the army embarked on an expedition to find him, which resulted in a massacre of indigenous people in isolation and the abduction of a family that was taken to the border town of La Pedrera.

At that point, the information about the existence of these peoples made the Colombian government consider the need to protect their territory. The Puré region is surrounded by vast indigenous territories (reserves), as is the great majority of the Colombian Amazon plains region. However, at the time, the concept of a reserve for the Yuri-Passe was discarded, given that there was a sense that there was no responsible entity with the capacity to protect the territory.

By 2002, Colombia had multiple reference points with regard to the devastating consequences of contact for isolated peoples, as with the case during the 1980s of the Nükak , who were forced into contact with missionaries, armed actors and settlers. The tragedies occasioned by contact have accompanied these peoples for the past forty years, including dispossession, exploitation, marginalization, forced recruitment, murder, prostitution, drug addiction, and alcoholism. These are impacts that they must confront while they currently resist incursions from outside their territory, which is increasingly being appropriated by third parties.

With this prelude, the Colombian government utilized the mandate of the National Parks System to “preserve the country´s biodiversity, environmental services and cultural diversity.” In 2002, the Puré River National Park [Parque Nacional Rio Puré] was established for the protection of the territory of the Yuri and Passe peoples in isolation.

Since that date, the Park officials, predominantly indigenous people from neighboring communities, have dedicated themselves with scarce resources to protecting this territory. It should be noted that there has been increased coordination with indigenous authorities to establish concerted prevention and protection efforts.

Over the years, researchers and traditional authorities of the indigenous peoples informed the government about signs of fourteen other peoples who live in isolation in the country.

By 2010, the researcher Roberto Franco-García, together with the National Parks System, the National University of Colombia and the NGO the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), had confirmed the existence of malocas belonging to these peoples in the Puré River. This assembly deployed a group of partners including governmental institutions, indigenous organizations and NGOs to propose to the government the establishment of a public policy that recognizes the existence of these groups in the country and enacts urgent protection measures.

In a few months, and due to publicity by journalists and anthropologists, these people were able to return to their territories, and since then there has been no news regarding these peoples. There are very few contact records or sightings of the Yuri-Passe. However, while timber merchants, drug-traffickers, miners and armed actors have taken advantage of these peoples’ resources in this territory, one way or another, they have felt the presence of this autonomous and resilient population.

In this respect, two national development plans have engaged the government with this task. Under the coordination of the Indigenous Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Interior, the aforementioned group established the baseline and roadmap for said public policy.

Regional and national indigenous organizations, the Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the Colombian Amazon (OPIAC), and the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC), lead the discussions with the government in the roundtable negotiations established for the Amazon region and the country, and arrange a roadmap for the formulation and consultation of said policy. After five years of meetings in malocas, consultations with indigenous peoples of neighboring communities, regional roundtables, meetings in the Amazon departments, international exchanges and other assemblies, Decree 1232 of 2018 was issued for the prevention of harm to and protection of the rights of isolated peoples in Colombia.

Thereafter, and by decision of the indigenous authorities, these groups have been referred to as peoples in a natural state. This policy intends to collect the lessons learned with the Nükak, the experience of neighboring countries and the international regulations in the field, as well as the UN’s guidelines from 2012 and the guidelines of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights from 2013.

The decree not only is a source of protection guidelines, but also creates a coordinated system between different levels of the State. It also establishes key principles to align all prevention and protection actions.

The protection system is comprised of a national commission, local (regional) committees, and intercultural technical groups, responsible for the territory’s protection. However, the decree lacks “foundations”, since no agreement was reached with the government to grant budget allocations or to create an office or a team that would be in charge of this issue within the Ministry of Interior, which is the body that coordinates the country’s indigenous public policy.

The decree creates prevention and protection mechanisms for these peoples, including regulations on research, prevention plans, societal awareness-building, monitoring and control, and risk and alert reports, and establishes the importance of recognizing specific indigenous planning tools as determinants in this protection. Therefore, life plans, environmental management plans and other internal regulation of indigenous authorities form part of this protection policy.

In this manner, the decree seeks to incorporate actions that have been carried out by the indigenous peoples who live adjacent to isolated peoples. Other cases to highlight are that of the Curare Los Ingleses reserve through the AIPEA indigenous association, the indigenous community of Manacaro, and the PANI indigenous association, which have been implementing joint surveillance actions in their territories since 2012. These actions have prevented threats to the territory of isolated peoples, encouraged self-designed education processes, negotiated agreements regarding natural resources, and carried out fauna monitoring for their protection. In 2015 and 2016, in the southern strip of the Putumayo River, coordinated action took place between the Tikuna authorities of the CIMTAR indigenous association, the National Parks System and the Ministry of Interior that prevented the entry of North American evangelical missionaries seeking to make contact with the Yuri and Passe.

Indigenous authorities of the Curare Los Ingleses reserve design protection for peoples in isolation. Juan Arredondo, ACT.

Even without a national protection policy, the National Parks System made progress in the implementation of the Puré River National Park´s management plan, whose mandate includes the safeguard of these territories. Its strategy consisting of control and surveillance, environmental education and coordination with indigenous authorities. A highlight, in 2015, was the construction of a checkpoint named Puerto Franco on the Puré River in the Colombian-Brazilian border, 600 kilometers and three days away from the nearest Colombian settlement. This checkpoint operated under the administration of the National Parks System and with the coordination of indigenous shamans involved with the protected area, until late 2020, when it was incinerated by illegal mining and drug trafficking groups.

Decree 1232 identifies the ancestral territories outlined in Decree 2333 of 2014 as a transient territorial category, which recognizes the ancestral possession of the indigenous peoples in isolation. However, thus far, the first of these categories has not been declared in Colombia.

A flaw of Decree 1232 is that due to political negotiations, and technical and budget constraints, the decree neither defines nor regulates the category of peoples in initial contact, leaving the Nükak once again without a policy. However, it establishes the need to establish contingency plans in the event of contact. These embrace coordination protocols and recommendations on how to proceed in different contact scenarios with the peoples in isolation, including their decision to make the contact continuous.

Over the past three years, the joy occasioned by this decree, endorsed by indigenous organizations, has been overshadowed by its slow implementation. The system has not been able to respond promptly to threats reported by indigenous communities and environmental authorities. Today, this territory is suffering its worst threats of the last twenty years. High-resolution satellite images from late April 2021 identified more than fifty illegal mining vessels in Brazil, just 24 kilometers from Colombia´s border.

Timber activities on the south of their territory, drug trafficking along the Puré River and a growing mining presence—due to the permissiveness of Brazilian President Bolsonaro’s government and the exorbitant price of gold in international markets—drives a growing misgovernment at the border and within the protected area.

The slow and disinterested implementation on the part of President Ivan Duque´s government with respect to the peace agreement established with the FARC guerrilla group has generated a set of new armed groups that fight for control of these territories, thus increasing insecurity, drug trafficking activities and other illegal economies in the region. Displacement, threats, extortions and the criminal eviction of public officials from ten protected areas of the Amazon region in 2020 are some of the consequences of this situation.

In August 2020, a convergence of mining and new armed groups took over the protected area, where a total of 25 dredgers, dragon dredgers and barges were recorded. Formal protests made by stakeholders of the system, but without implementation of the mechanisms of Decree 1232, resulted in a coordinated operation of the armed forces in which more than ten dragon dredgers (oversized barges to extract material from the river) were destroyed in a controlled manner.

An important achievement and challenge of Decree 1232 is widespread indigenous participation in the decision-making process at every level. Their equal participation, and in some cases majority participation, manifests itself at all three levels of the system. However, the limitations associated with high mobility costs in the rainforest, the lack of government assistance with respect to the Covid-19 emergency in territories adjacent to peoples in isolation, and an unwillingness and lack of resources to include the active participation of local authorities in regional and national discussions have slowed the decree’s implementation.

The government’s slow operation continues to delay the implementation of this decree. Although the implementation has not been disregarded, the sluggishness of the processes and an unwillingness to initiate the protection systems are well known, in a parallel with the peace accords. Had it not been for the pressures and negotiations of indigenous organizations and civil society, the processes would be even more incipient than they currently are.

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.

[…] a groundbreaking move, the Colombian government has taken an unprecedented step to protect Indigenous Peoples Living in Isolation—with Indigenous allies, the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), and a coalition of partners playing […]