A Promise to Kwamalasamutu

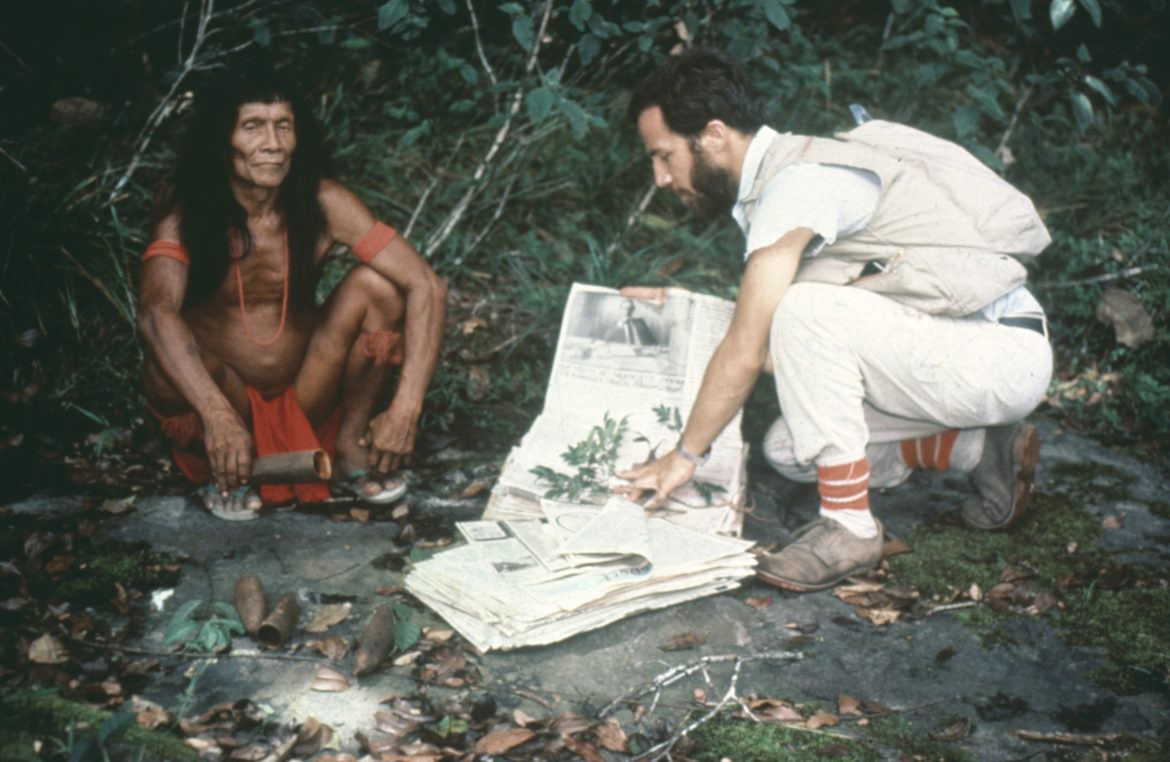

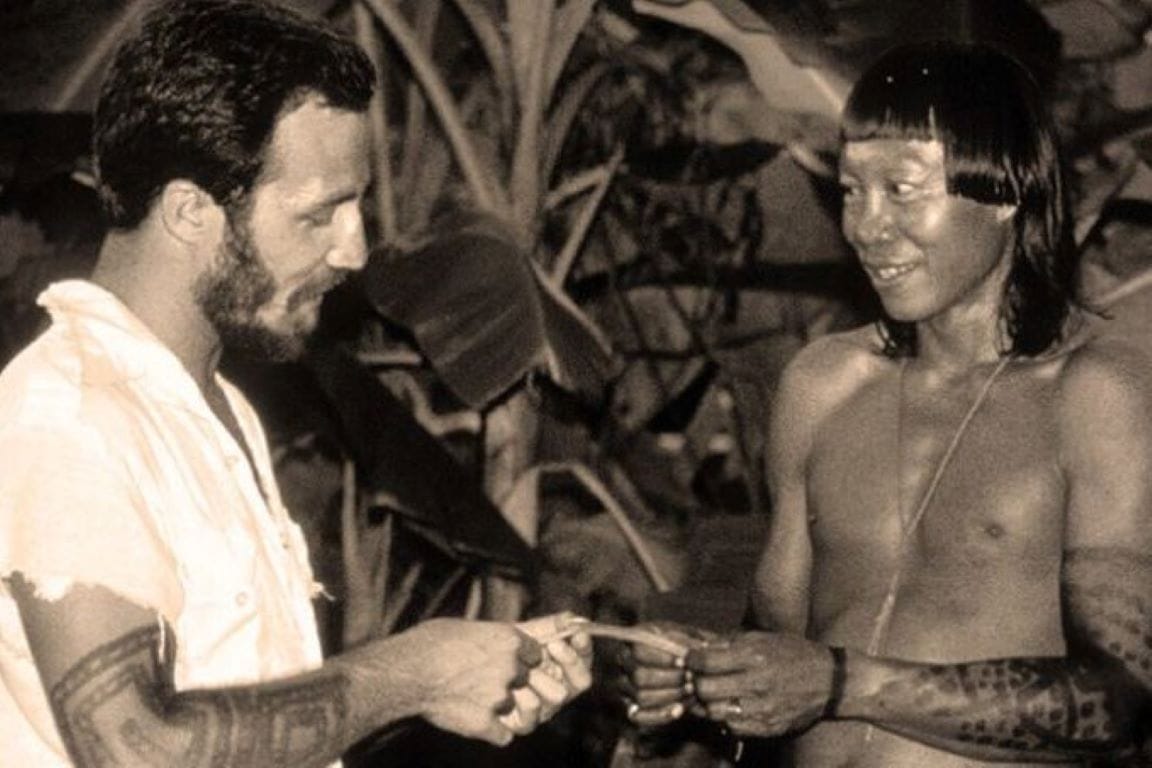

Long before Liliana and I founded the Amazon Conservation Team in 1996, I saw firsthand as an ethnobotany student the many assaults on indigenous cultures and territories in the tropical Americas – from fundamentalist missionaries, corporate agriculture, and destructive extractive industries to the ever-encroaching and seductive allure of Western globalization. On a research trip in 1982, I visited the indigenous village of Kwamalasamutu in south Suriname, the capital of the Trio indigenous nation and home to over a dozen other indigenous groups. During this visit, I made what proved to be quite a consequential promise. I gave the paramount chief my word that the medicinal plant knowledge I learned from his peoples would be returned to him in written form … in their language. At that time, I was uncertain that such a compilation would have any impact.

Return to the Community

I returned to Kwamalasamutu several times a year for most of the ensuing decade. On almost every visit, I was shocked to see how much the community had changed and the interest in their own culture had diminished. Colorful red breechcloths and beautiful seed jewelry had been exchanged for ill-fitting, Western hand-me-downs, unsuitable for a tropical climate. The older men who once took pride in maintaining long and lustrous locks had hacked off their hair in order to appear like the Western men in magazines left by outsiders. And several of my friends told me they no longer made curare or hunted with bows and arrows; instead, they now used shotguns. Gone were the toucan-feather headpieces, red face paint and blue body paint once worn with pride. Not only in Kwamalasamutu, but across indigenous communities in the northeastern and northwestern Amazon, I saw an almost unilateral cultural change and sometimes forced assimilation toward Western ideals. Indigenous peoples, especially school-age children, were taught that their traditional ways of life and knowing were inferior to that of the ever-dominant Western world — resulting in further loss of cultural practices and knowledge, and a devaluation of the traditional medicine men and women or shamans (known in the Trio language as pee-yiis).

The Importance of the Shaman

Shamans represent an unbroken lineage of tradition that stretches back countless generations. Through trial and error over millennia, rainforest dwelling peoples have built up an enormous storehouse of information on the healing properties of the native flora, fauna, and fungi. And no one in Amazonian indigenous communities understands these plants better than the shaman who developed treatments and cures with them — for everything from foot rot to dandruff.

When shamans die without a protégé — a reality that was becoming more and more common in the Amazon — the loss of traditional knowledge culturally impoverishes the community. And at the global level, humanity loses irreplaceable cultural diversity and unique cosmologies.

Mark J. Plotkin, co-founder & President of the amazon conservation team

Validation of Local Knowledge

On my 16th visit to Kwamalasamutu, I was able to fulfill my promise: I handed the chief a 200-page manuscript detailing everything that I had learned about the medicinal plants of his peoples. The chief received it, smiled politely, and handed it to a member of his entourage. I was a bit crestfallen, because I had handed him what – after the Bible – was the second book ever produced in the Trio language.

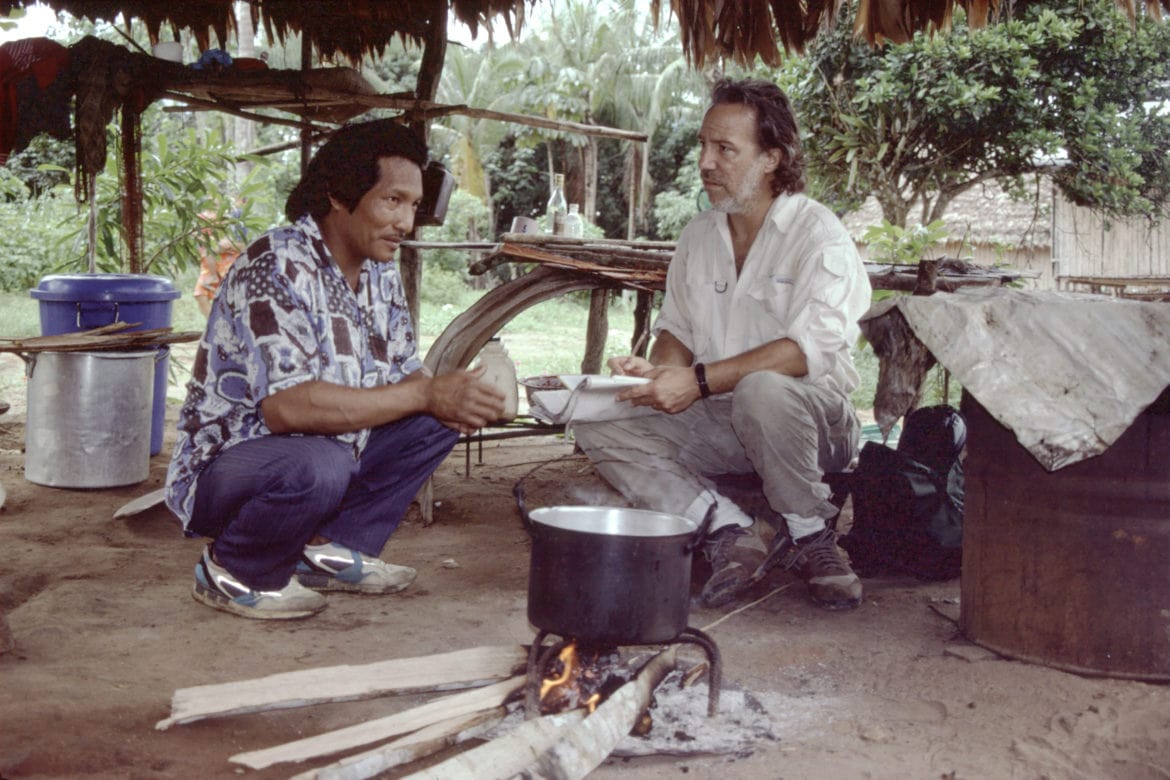

On another significant visit to the village not long after, I was joined by the prominent Costa Rican herbalist and fellow ethnobotanist Luis Poveda. One scorching afternoon, we returned to the settlement after a morning of collecting medicinal plants in the forest. While we were all seated around a table examining the specimens we had collected, the paramount chief unexpectedly entered the dwelling we were in and asked if he could make a request. The chief was a fundamentalist Christian and had never showed any personal interest in my research, vaguely grumbling on several occasions that the old ways were the devil’s ways, so I listened with some trepidation.

He said that he had a request for the visitor from Costa Rica. His six-year old granddaughter was severely constipated, and the clinic established by the missionaries had run out of medicine. Since Luis was supposed to be knowledgeable about medicinal herbs, did he recognize any local plants that could be used to help his granddaughter? All the while, the Trio shaman, Amopadifa, was watching. Happy to be of assistance, Luis promptly walked into the forest and quickly produced a plant-based laxative that alleviated the granddaughter’s digestive issue.

Impressed, the chief came back the following day. It seems that he had been out hunting that morning and had held the shotgun incorrectly, such that the discharge of the gun had badly bruised his shoulder. Did Luis know of any plants that could alleviate the pain?

The herbalist was just about to go into the forest to search when the shaman Amopadifa stood up and began responding angrily to the chief. He was infuriated that the chief was requesting assistance from a foreigner when he himself could produce all these same plant-based medicines – an insult added to injury after years of watching the chief dismiss the traditional medicine of his people and trusting blindly in Western medicines. He – Amopadifa –knew how to treat the chief’s bruise and could have cured the chief’s granddaughter the day before. He grabbed his machete and headed into the forest.

A Living Tradition Revived

The following day, after being healed by Amopadifa’s medicine, the chief again said he wished to speak to us. Here are his words, which I will never forget: “The white man lied to us. He said our medicines were weak, and using them was the devil’s work. But who made the forest? God made the forest. Therefore, he made all the medicines we need within it! It is our duty to protect the forest and to protect and use these medicines.”

Before this encounter, I had long worried that the cultural integrity of these people might not survive. But my pessimism was premature. No longer should a foreign researcher like me need to record and preserve the traditional practices. My friends Koita and Kamainja had been chosen by the chief to serve as shamans’ apprentices. The traditional knowledge would now be passed on within the community from elder to student, shaman to apprentice.

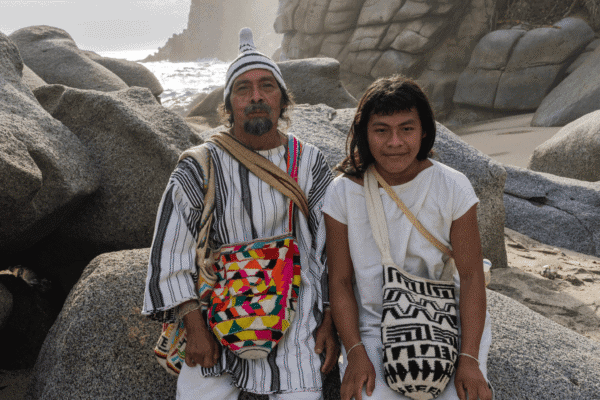

The Founding of ACT’s Shamans and Apprentices Program

Informed by these experiences in Kwamalasamutu, ACT launched its formal Shamans and Apprentices Program – one of the organization’s foundational initiatives. By fostering the creation of community medicinal plant books and supporting the living tradition of shamans teaching their apprentices, ACT went on to replicate this program in four Surinamese villages. ACT provides modest stipends to the shamans and apprentices, necessary physical equipment, and other guidance as needed. We follow the lead of the indigenous peoples and support them in their journey of cultural self-determination. Eventually, we went on to construct five associated traditional medicine clinics in the hinterland of Suriname that are directed and operated by the elder shamans. These clinics are near Western health facilities and act as a complementary form of culturally specific healthcare.

A Hopeful Beginning

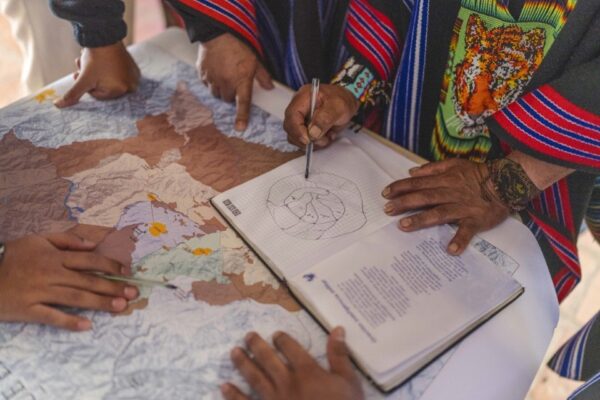

The success of the Shamans and Apprentices program was just the beginning of the pioneering biocultural conservation work that ACT has gone on to do. In the spirit of supporting communities in their own efforts — as opposed to implementing foreign, top-down initiatives — ACT sought to secure culturally appropriate means for human and environmental wellbeing, and increase recognition of indigenous culture and self-determination. In this way, we were able to merge the strengths and tools of the Western world in a way that complements but doesn’t dominate the ideals and goals of the local community. This marriage of technology and indigenous wisdom eventually laid the groundwork for our cultural and territorial mapping, an initiative that has gone on to become one of ACT’s greatest conservation strengths.

Related Blog Posts

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.

I think the photo of laughter in the forest speaks volumes about how Mark Plotkin and Amazon Conservation Team have been so effective–through a deep and genuine humanity. I am humbled by the opportunity to support, even in the most modest way, the efforts of this phenomenal organization.