Home to just 5% of the global population, South America has been suffering a third of the world’s recent coronavirus deaths. Months of strict lockdowns failed to flatten the curve of infections as they did in Europe and East Asia, and the continent faces the worst of both worlds: a heavy human toll and crippling economic damage. With a predicted reduction of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for 2020 of 9.4%, South America’s fall in economic activity is of such a magnitude that its GDP per capita will end 2020 at a level similar to what was seen in 2010 – meaning that there will be a setback of a decade in income levels per inhabitant. Early optimism that the region might escape the worst of the pandemic quickly gave way to the stark reality of sharply rising death tolls. In terms of deaths from COVID-19, Brazil is now the worst affected country in the developing world. Adjusting for population size, the world’s hardest-hit countries are Peru and Ecuador, each of which have seen more than 1,000 excess deaths per million inhabitants.

Far from the initial COVID-19 epicenters in Europe and the U.S., Amazonian indigenous communities expected to stay safe from the pandemic, tucked away as they are in remote jungle towns and villages. But when the virus arrived, it struck rapidly and at the very core of the communities, the elders. The impact of COVID-19 has been devastating to the indigenous peoples of the Amazon, with 63,181 confirmed cases and 1,896 deaths from 248 indigenous groups of the region as of September 30, 2020.

The crisis has exposed a lack of resilience in economies and health systems around the region. This is alarming, as remote areas of the continent and specifically the Amazon have weak health systems compounded by low access to modern and reliable electricity. Nevertheless, the crisis has created an opening for governments and organizations to facilitate energy access in these areas by focusing on clean and renewable energy technologies.

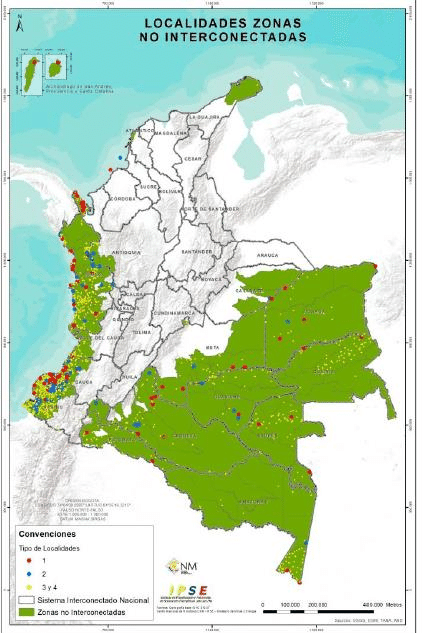

For example, energy provision in Colombia’s Non-Interconnected Zones (ZNIs)—areas where the centralized national electricity grid cannot reach—continues to be a challenge due to technical, economic, social, and environmental sustainability factors. Representing 52% of the national territory, these areas usually have partial or no electricity coverage, with energy services generated under a highly subsidized business model based on traditional, environmentally unfriendly technologies. The ZNIs embrace a population of close to 1.8 million inhabitants spread across 1,700 settlements, with only 35% of the population having access to electricity services, a number that has remained stagnant for almost a decade. The electricity capacity that does exist in ZNIs is almost entirely diesel-generated (96%), followed by 3% from small hydropower, and 1% from solar energy and other energy sources. There is an enormous growth and impact potential for renewable energy in these regions.

As part of a broader initiative in partnership with the C.S. Mott Foundation, which has brought solar energy access to nearly 5,500 indigenous and rural people in some of the Amazon’s most remote and energy poor communities, the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) was able to install more than 570 solar energy systems in the Colombian Amazon, a crucial resource due to the pandemic’s interruption of travel and supply chains. Through this effort, ACT was able to bring solar energy to hundreds of indigenous and peasant families during the Covid-19 pandemic. “As a program officer at the C.S. Mott Foundation, I am privileged to be able to support programs to expand renewable, offgrid energy solutions for remote and isolated communities in the Amazon,” said Program Officer Traci Romine. “Bringing light to people living in darkness can help them weather storms such as the new coronavirus pandemic.”

Most of the supported families had no sustained electricity at the time and weren’t able to light their homes at night. Without access to reliable electricity, community members carried out work, and treated their sick, in near darkness, relying on kerosene lanterns, candles, and biomass. Crucial for increased community resilience during the pandemic, the solar energy systems have reduced household air pollution, a factor that increases the risk of severe illness from Covid-19. ACT field staff continue to install solar energy systems in the region. “These solar lights will greatly help my family to take on domestic chores and livelihood activities at night,” said Nataly Garcia, a farmer in the El Jardin village community of San José del Fragua.

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.