In his 1700 last will and testament, prolific Inga healer and leader “Taita” Carlos Tamoabioy asserted his wish for the lands of the Sibundoy Valley to be cared for by his peoples. Knowledgeable about the Spanish colonists’ language of legal ownership, he provided the deed to the land, including its geographic boundaries.

The wish expressed in the testament has become a cultural pillar that gives direction to the Inga and kamëntsá peoples of the Sibundoy Valley, as well as a legal legitimizer of territorial claims made—and won—over 300 years later.

Benjamin Jacanamijoy tells of Carlos Tamoabioy’s testament:

“This is the land that I leave to you, my descendants, to care for it, protect it and benefit from it until the end of time. Nothing and no one should interfere with this plan. You must live in unity and never forget that you are never alone, for the rivers, the forests, the mountains and all that exists are part of our family. They will be your protectors.”

The Place of Origin

The foothills of the Andes descend to the Amazon rainforest in a stunning display of life. Here headwaters of major Amazon tributaries are born, one of the world’s highest concentrations of medicinal plants flourish, and nearly one thousand bird species soar through vast range of altitudes. It is home to the Sibundoy Valley—a bowl-shaped depression that is encircled by steep mountains and is the sacred place of origin for the Inga and kamëntsá indigenous communities.

The deep relationship between the people and territory is reflected in the kamëntsá language. The suffix -oy indicates place of origin, as in the territory’s name itself, Sibundoy, and most kamëntsá last names like Mutumabajoy or Chindoy. Belonging is embedded within identification.

The blended Inga and kamëntsá culture is largely intact and carries some of Colombia’s strongest living indigenous traditions—most of all, profound respect for Tbatsanamamá, Mother Earth, and all of her gifts, including plant medicines. The culture has survived through colonization commencing in the 1500s, religious missions and interventions peaking in the 1900s, and violence and instability through today.

For Future Generations

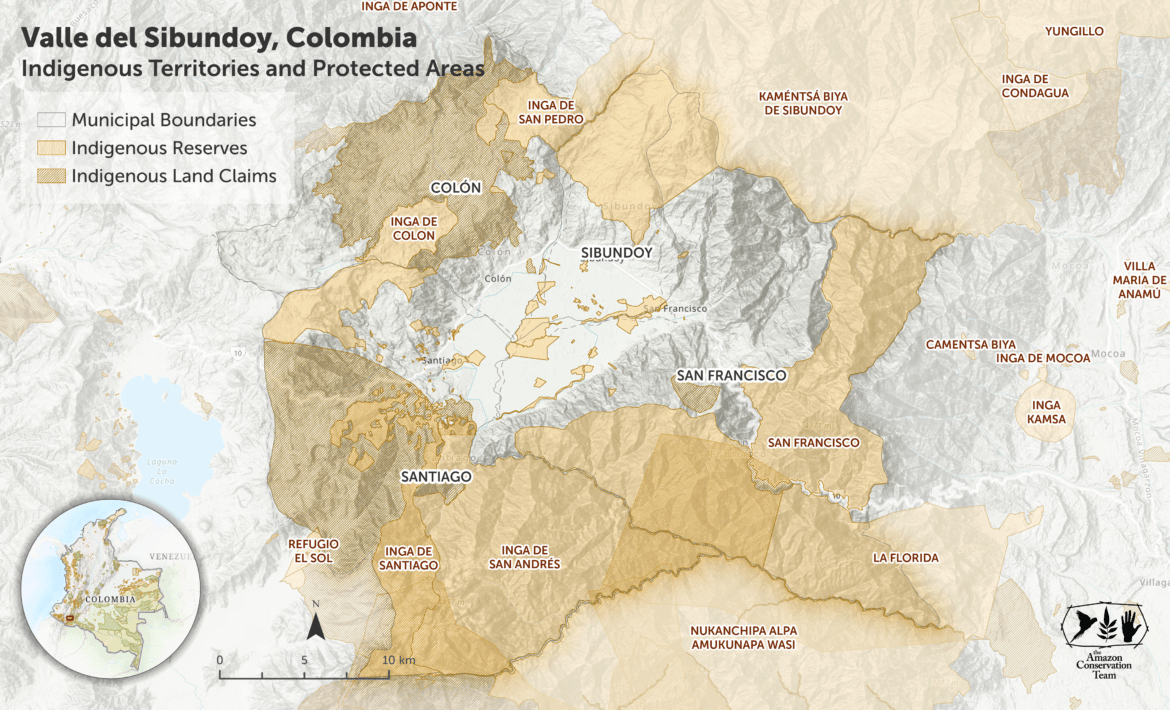

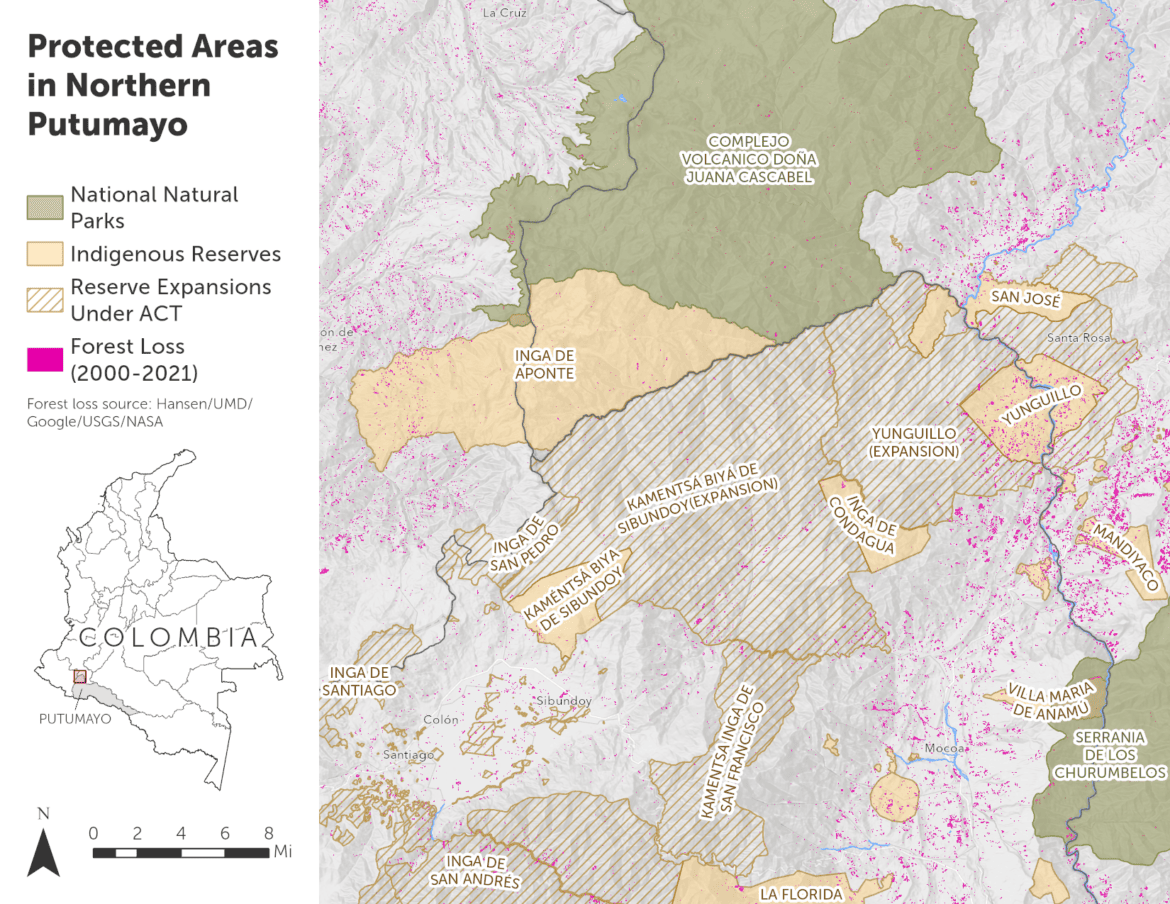

Since 2012, the Inga and kamëntsá communities have partnered with ACT to push forward their struggle to reclaim the Sibundoy Valley. ACT provides essential support with respect to coordination and technical demands such as topographic and socioeconomic studies.

Together, we have achieved the creation of five reserves and the expansion of one reserve encircling the valley and connecting to a vast mosaic of indigenous reserves and protected areas. All in all, we have facilitated the return of nearly 240,000 acres of forest to indigenous care, benefitting over 23,000 Inga and kamëntsá individuals with unimpeded access to their ancestral territory and sacred sites.

With each reserve, the territory—the physical landscape and ecosystems, and the cultures, knowledge systems, and values of their original peoples—is protected under the full autonomous management of their indigenous communities.

But the dreams of these reserves began at least ten generations ago, and the legal process decades ago. For example, Santiago first requested its reserve constitution in 1989, and it came to pass in 2019—30 years later.

Jacinta Jamioy reflects on the importance of the official declaration of the Santiago Indigenous Territory:

“If you don’t have territory, there is no life. We protect the mountains because there is water, the trees because they give us oxygen, and the plains because there, we can plant and grow our food. It is a life process, which not only serves those of us who are in this present moment, but also our future generations. That is why it is a life process.”

“The process continues. The struggle continues, the resistance continues, in the Sibundoy Valley.”

-Jacinta Jamioy

Today, ACT continues to support the Inga and kamëntsá in further consolidating their territories by purchasing lands that connect critical ecosystems and sacred sites. ACT also supports these communities in the participatory drafting of their life plans, which aim to protect their vast territories from threats such as roads or hydroelectric dams that cut through sensitive ecosystems. With these skills and a long-term commitment, communities are ensuring that their forests and water reservoirs are not snapped up by land-grabbers or rapacious companies, all while maintaining a relatively traditional lifestyle of their own choosing.

Real, enduring change requires a long-term commitment. The Inga and kamëntsá have resisted and persisted for more than 500 years to protect their culture and reclaim their forests and their most sacred place of origin. ACT will continue to stand alongside them.

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.