Curare is a plant-based arrow poison perfected over centuries by Indigenous peoples of the Amazonia. Applied to the tips of both blowgun darts and arrows, it induces profound muscle relaxation, ultimately stopping breathing by paralyzing the diaphragm. This remarkable botanical technology was central to subsistence hunting in tropical rainforests, where dense canopy and elusive prey demanded precision rather than brute force.

Beyond its role in Indigenous life, curare fascinated and frightened European explorers, physicians, and scientists. Its ability to selectively paralyze muscles without affecting consciousness profoundly influenced early research into neuromuscular physiology and later became foundational to modern anesthesia and surgery.

What Is Curare—and Why Did It Matter?

When Spanish conquistadors entered the Americas, they brought overwhelming advantages: steel weapons, firearms, horses, and immunity to many Old World diseases. Indigenous peoples of the Amazon had none of these. Yet they possessed a different kind of power—deep botanical knowledge, refined over millennia. One of its most formidable expressions was arrow poison.

Curare was not merely a weapon; it was a technology of survival. In an environment where large terrestrial game is scarce and visibility limited, curare enabled hunters to efficiently harvest protein from the forest canopy. Its effectiveness shaped settlement patterns, hunting strategies, and cultural traditions across vast regions of South America.

How Indigenous Amazonians Used Curare

Hunting Practice and Target Animals

Curare was overwhelmingly a hunting poison, not primarily a weapon of war. It was most commonly applied to blowgun darts, which were light, aerodynamic, and capable of remarkable accuracy over long distances.

Hunters targeted arboreal animals—especially monkeys and birds—that would otherwise be difficult to capture. A bird struck by a curare dart might fly briefly, only to lose muscle control and tumble from the canopy. This allowed hunters to retrieve prey intact, without damaging meat or feathers.

Primates presented a different challenge: a monkey shot with a blowdart or an arrow might wrap its tail around the tree branch to prevent falling from the canopy. By coating the weapon with a muscle relaxant, the game animal lost the ability to hold onto the branch or limb.

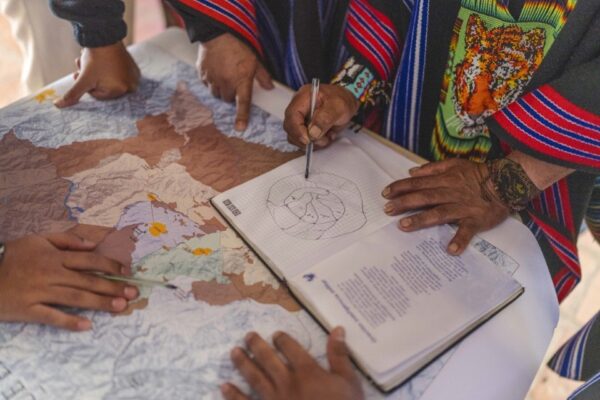

Hunting with curare required extraordinary skill, patience, and ecological knowledge. Dart makers, poison specialists, and hunters often held distinct roles, and the preparation of curare was frequently surrounded by ritual and secrecy.

Why Curare Was Seldom a Weapon of War

Despite its lethality, curare was not as efficient or effective in warfare. Its effects are not instantaneous; paralysis develops over minutes, not seconds. In close combat, this delay could be fatal to the attacker.

For this reason, many Amazonian societies preferred other means in conflict—clubs, spears, or ambush tactics requiring immediate incapacitation. In some cultures, there was also a moral or ritual distinction between poisons used for animals and methods used to kill humans. Curare, associated with hunting and subsistence, was sometimes considered inappropriate or dangerous to use against people.

Nonetheless, there are repeated indications that curare-tipped arrows were sometimes employed in conflicts. Photos exist of the Karijona people in Colombia and the Wayana people wearing the equivalent of “body armor” made from bark, employed to prevent wounds from poison-tipped arrows.

Safety: Poison on Meat, but Not When Eaten

One of curare’s most remarkable properties is that it is only toxic if it enters the bloodstream. When swallowed, it is broken down by digestive enzymes into harmless compounds.

This meant that animals killed with curare could be eaten safely—an essential feature for a subsistence poison. Indigenous hunters understood this pharmacology empirically long before Western science explained it, demonstrating a sophisticated grasp of cause and effect in plant chemistry.

How Curare Works

Curare acts at the neuromuscular junction, blocking the transmission of nerve signals to muscles. The brain remains fully conscious, but muscles—including those required for breathing—can no longer contract.

Death occurs through asphyxiation, unless artificial respiration is provided. This precise mechanism explains both its effectiveness in hunting and its later importance in medicine. Unlike poisons that cause tissue damage or cardiac failure, curare produces clean, reversible muscle paralysis—an insight that revolutionized surgery centuries later.

From Rainforest to Research Lab: Early Observations

European awareness of curare dates to the 18th and early 19th centuries. Explorer-naturalists such as Charles Marie de La Condamine (from France) and Charles Waterton (from England) carefully documented its preparation and effects.

Waterton, in particular, conducted daring self-experiments and animal trials. He even explored curare as a possible treatment for rabies and tetanus, intuitively grasping its muscle-relaxing potential. Though these medical applications were premature, his observations laid critical groundwork for later pharmacology.

What struck Europeans most was the variability of curare. Some preparations involved dozens of plants, others only a few. Potency differed dramatically from one region—or even one poison maker—to another.

Plants and Preparation: The Science Behind Curare

Key Plant Families and Regional Variations

Curare is not a single substance but a family of preparations. In the eastern Amazon and Guiana Shield, it was often derived from Strychnos lianas (family Loganiaceae). In western Amazonia, preparations more commonly relied on moonseed family lianas (e.g., Chondrodendron tomentosum, Menispermaceae), particularly species rich in alkaloids like tubocurarine.

Different regions produced chemically distinct curare types, each reflecting local flora and cultural tradition.

Additives That Increase Potency

Curare recipes made from Strychnos lianas frequently included plants from the pepper family (Piperaceae). These additives were not toxic themselves, but they enhanced the absorption and bioavailability of the active compounds—an early example of pharmacological synergy.

Such combinations demonstrate that Indigenous poison makers were not merely boiling plants at random: they were conducting sophisticated empirical chemistry.

Knowledge at Risk

As blowgun hunting declines and modern weapons spread, the knowledge of curare preparation is rapidly disappearing. Much of this expertise was transmitted orally and restricted to specialists. With its loss may vanish not only cultural heritage, but also potential medical insights still unexplored by science.

Key Takeaways

• Curare is an Amazonian arrow poison used mainly for hunting.

• It causes paralysis of muscles, including the diaphragm, leading to suffocation.

• Meat from animals killed with curare is safe to eat because digestion neutralizes the poison.

• Recipes varied widely among tribes; preparation skill was crucial.

• Curare attracted scientific interest for its unique muscle-relaxing properties.

• Additives such as Piperaceae plants enhanced its effectiveness.

• Traditional curare knowledge is rapidly disappearing.

FAQs

Was curare used in war?

Seldom. While occasionally used in ambushes, it was primarily a hunting poison. Its delayed effect made it less appealing for combat.

How does curare kill?

By blocking nerve signals to muscles, especially the diaphragm, preventing breathing.

Is curare dangerous if eaten?

No. It is harmless when digested and only works if it enters the bloodstream.

What plants were used to make curare?

Common sources included Strychnos and moonseed family lianas, along with additives like Piperaceae plants.

Why is curare knowledge disappearing?

The prevalence and availability of shotguns and the decline of traditional hunting have eroded intergenerational transmission of this and much other ethnobotanical knowledge.

Credit: Dr. Mark J. Plotkin, from his book “The Amazon: What Everyone Needs to Know“

Don’t miss these powerful stories and updates. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.