The last country in tropical South America yet to guarantee collective land tenure for its indigenous peoples

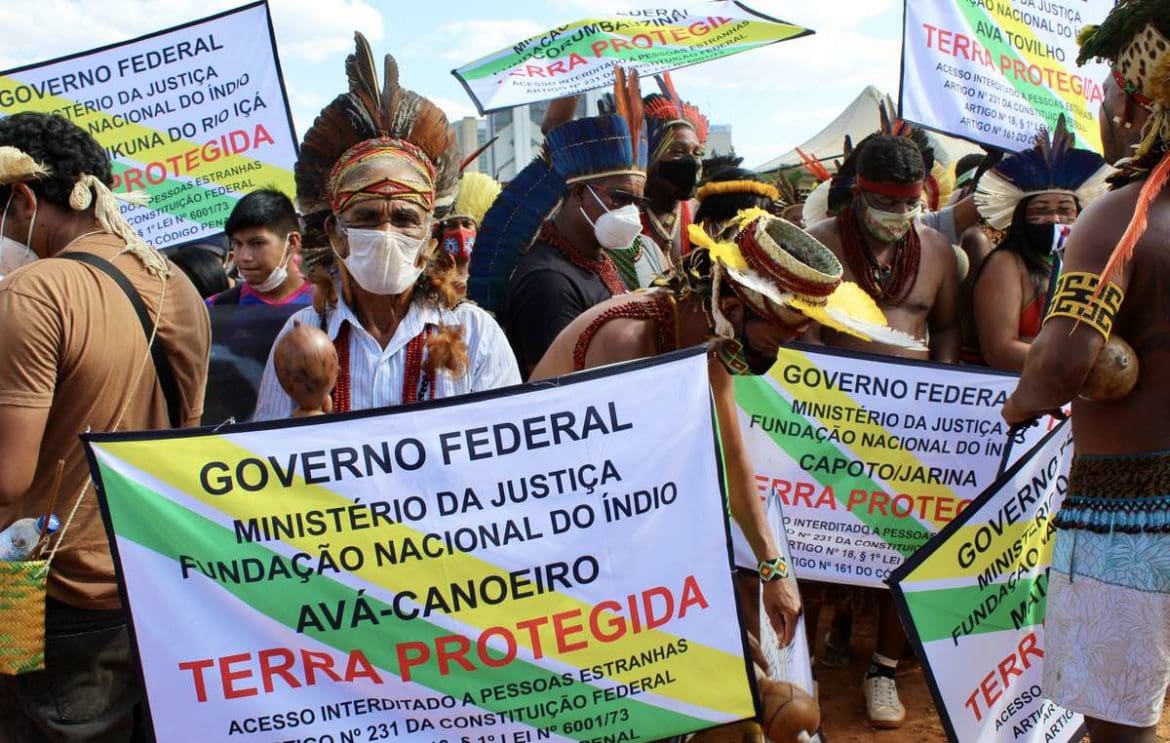

Recent years have brought a global explosion of interest in and consciousness of indigenous rights, primarily centered on protecting indigenous land tenure. Across the Americas, the public has witnessed historic indigenous mobilizations to uphold land rights in the face of external threats – such as the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota and the Struggle for Life mobilization in Brasilia. In the small nation of Suriname, nestled on the northeast coast of South America, there is renewed political momentum, not to uphold existing rights, but to finally establish indigenous land rights in 2022. In fact, Suriname is the only country in tropical South America that has not yet legally guaranteed the collective rights of indigenous peoples to the territories to which they and their ancestors have deep and long-held ties.

On several fronts, the young nation of Suriname has yet to acknowledge basic rights for indigenous peoples. The country is one of the few in South America that has not ratified ILO Convention 169, which recognizes indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination within a nation-state and sets standards for national governments regarding indigenous peoples’ political, socio-cultural, and economic rights. Additionally, the legislative system of Suriname is based on colonial-era policy that does not recognize any specific rights for indigenous peoples.

Where it began

In fact, colonial rule ended relatively recently, and Suriname did not become a sovereign state until 1975. The grassroots fight by indigenous activists to establish land rights began quickly thereafter. In December 1976, during a four-day march to Paramaribo, the national capital, indigenous men and women rallied around the slogan “land rights are human rights” – marking the beginning of a decades-long struggle. Across the generations, the battle for legal recognition of land rights has since continued in multiple forms with many different political actors. On several occasions, the country came close to passing new laws that would amend the legal shortcomings, but without fruition.

Why it matters

A principal reason that this legislation is so critical for Suriname’s indigenous peoples is the indispensability of their territory to their collective cultural and physical wellbeing. Many aspects of indigenous Amazonian cultures are intricately linked to the rainforest – including food production, medicine, and spirituality. Without formal recognition and legal guarantees, indigenous peoples lack the authority to manage and protect the territories and forests that are core to their identities, their ways of life, and their very existence.

In South America, human rights violations, pollution, and destruction of indigenous territories and natural resources are ever-increasing, primarily for the purpose of extractive profit-driven industries such as mining, logging, cattle ranching, and monoculture production. In contrast, it has been well documented that in places where indigenous peoples have recognized land tenure and can exercise self-determination over their territory, rates of deforestation decrease, and forests are better conserved, oftentimes better than national parks. Furthermore, approximately 80% of the world’s remaining terrestrial biodiversity is found within the territories of indigenous peoples.

The support of ACT

Despite the challenges associated with the lack of indigenous land rights, ACT has been working with the indigenous peoples of southern Suriname since 2002 to protect their forests, support indigenous self-determination, and promote initiatives to recover and revitalize indigenous knowledge. And in recent years, ACT has been working at the grassroots level with indigenous communities, and at the institutional level with the regional and national governments, to raise public awareness and provide technical and legal support to finally secure indigenous land rights and formal recognition of indigenous-led environmental management.

What comes next

Now the country again arrives at a familiar moment, as new land rights legislation has been drafted and is officially scheduled to soon be brought before Suriname’s parliament for a vote. This time around, the legislation enjoys more political momentum and will. ACT remains cautiously optimistic, but regardless of the outcome, we will continue to stand with and support our indigenous partners in Suriname in protecting their territories and conserving the tropical forests they call home.

Click here to learn more about our work in Suriname.

This blog is the first in a series of pieces about the upcoming vote on collective land rights in the Surinamese parliament. Stay tuned to learn about how this bill would also formally recognize the collective lands of Maroon peoples, descendants of formerly enslaved peoples who escaped the Dutch plantations for the rainforest hundreds of years ago.

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.