Guardians of the Forest: Who are isolated Indigenous peoples?

In some of the most pristine and remote forests of the Amazon live Indigenous peoples who have little to no contact with the outside world. They have no cellphones, cars, or computers, but they hold deep knowledge of the forest and an interconnected relationship with the territories they’ve called home for generations.

More isolated Indigenous peoples live in the Amazon and Gran Chaco regions than anywhere else in the world. In Spanish, these groups are often referred to by the acronym PIACI, which translates to Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact. A report earlier this year from the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) and our partners found that there are 188 known Indigenous groups living in isolation in South America.

Often, their decision to live in isolation is a survival strategy. Centuries of colonialism and violent contact with Christian missionaries, rubber barons, and now illegal miners, loggers, and oil and gas drillers have driven these Indigenous communities further into the rainforest, away from these mounting threats to their livelihoods and biodiverse ecosystems.

Why isolation is protection

The Amazon Conservation Team is actively working to protect about a dozen of these groups in Colombia and Brazil, and is also working indirectly to protect about 25 more in partnership with national, regional and local Indigenous insitutions in Peru.

“If we don’t officially recognize and protect their territories, they are completely wide open to any sort of threats, like forced contact or invasion of their territories,” says Adam Bauer-Goulden, a contractor with ACT based in Peru. “It would basically mean their extinction.”

To use the term extinction is not an exaggeration. It’s not only violent clashes that pose a threat—a common cold could be a catastrophic disease for those who have never been exposed to it. This is why ACT and our partners believe strongly that isolation is protection, and a human right that must be respected.

There are currently protections for PIACI in seven countries in the region —Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Venezuela, and Bolivia. According to the recent report from the International Working Group of Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact (GTI-PIACI), for which ACT serves as the General Secretariat, only 60 of the 188 known isolated groups are officially recognized by the state. And even those legal protections don’t always guarantee that Indigenous peoples in isolation will remain undisturbed.

Bauer-Goulden says that Peru, for example, is ahead of many countries when it comes to passing legislation, but the implementation is inconsistent. “They have really good legislation,” Adam says. “It’s just often not complied with.”

He also notes that oil, gas and logging concessions frequently overlap with PIACI territories. Research from Earth Insight found that last year, proposed oil and gas blocks threatened about 20 percent of the reserves of isolated Indigenous communities. And Peru’s legislature is currently considering a controversial bill that would open areas such as national parks, historical and national sanctuaries, and communal reserves to resource extraction.

“Our territory is our life, but the government is auctioning off plots. It is a great invasion with a grave impact,” Julio Cusurichi, a member of the Shipibo-Conibo people and an Indigenous leader from the Andean Amazon, told The Guardian last year.

How to protect isolated Indigenous peoples without contact

The Amazon Conservation Team works with leaders such as Cusurichi, and other Indigenous associations like the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP), to help determine which territories are home to PIACI.

“Almost all the communities that are adjacent know about them. In fact, they know way more about them than any person coming from the outside,” says Bauer-Goulden.

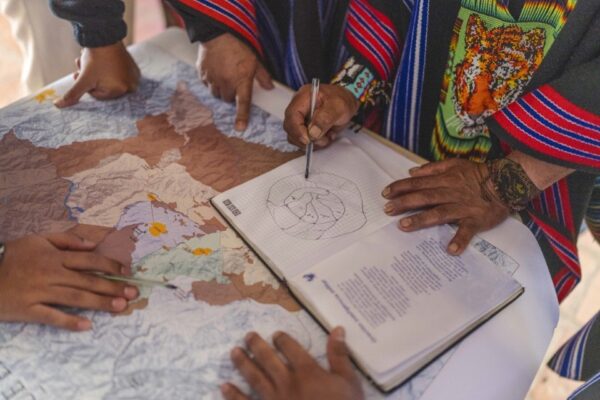

The first step is to host community meetings with Indigenous groups who are living in contact with society, and to document testimonies and stories that could help establish the presence of their isolated Indigenous neighbors. Proving their existence triggers legislation for protective designations in most Amazonian countries. This type of collaboration is at the heart of ACT’s work across the Amazon, and is something Bauer-Goulden helps to lead in Peru and other regions where PIACI have been documented.

The knowledge that ACT gathers from Indigenous testimonies about where isolated groups might be located is then mapped. “The next step is satellite images,” Bauer-Goulden says. “And you hope you find longhouses.”

For the last decade, the Amazon Conservation Team has been a nonprofit Purpose Partner for the Colorado-based satellite technology company Maxar. The images from real-time satellite technology, combined with Indigenous knowledge, help to establish the presence of the PIACI and their territory without invasive flyovers from planes.

A Maxar satellite image taken in 2019 of the Rio Pure in Colombian Amazon. The region is home to isolated Indigenous groups who are increasingly threatened from activities like illegal mining. Maxar images have helped ACT identify more than 800 illegal mining barges since 2020. Photo credit: ACT/Maxar

Because flyovers can be so disruptive to isolated communities—sometimes even leading them to abandon their longhouses and relocate—ACT makes every effort to avoid them. When a flyover is conducted, the plane never flies lower than 400 meters, and never circles more than twice.

Bauer-Goulden also says that the technology from Maxar has allowed ACT to make comparisons between the past and present presence of PIACI, which has revealed some disturbing trends.

“We’ll use Maxar images to show that they had longhouses here before, but now those longhouses have been abandoned. And that could be due to these encroaching threats, like logging and mining.” This by no means signifies these are no longer their territories, Bauer-Goulden stresses. He says it’s important to recognize that while they may have abandoned their buildings to become more mobile, they regularly return to these areas to hunt and gather food. Just as recognizing PIACI in these regions can lead to legal protections, the opposite is also true. Suspected abandonment could mean that the government no longer protects these rainforest regions, even when isolated groups never truly left.

ACT is working hard to keep PIACI in their ancestral lands, and is seeing success. Last year, we supported the Curare Los Ingleses Indigenous Reserve to help establish the presence of their neighbors, the Yuri-Passe, who were living in isolation in the Colombian Amazon. These efforts led the Colombian government to legally establish a 2.7-million-acre protected area for the Yuri-Passe, along with an additional buffer zone. The protected area will not only prevent dangerous and unwanted contact with isolated groups, but will also protect some of the most biodiverse and critical ecosystems in the world.

The Amazon Conservation Team and our Indigenous and local partners in the Amazon will be taking this message of PIACI protection to the COP30 UN Climate Conference in Brazil this November. As Bauer-Goulden summarizes:

“The ecosystems need the people, and the people need the ecosystems.”

Don’t miss these powerful stories and updates. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.