Thousands of years ago, when jaguar populations were at their peak, they could be found hunting along the coasts across the Americas. After colonization, these apex predators lost access to the sea in much the same way many Indigenous communities did. Today, the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) is working to research and restore this natural balance.

“We’re reconnecting the areas from the mountains to the ocean for the Indigenous communities the same way we’re doing it with the jaguar,” said Juan Carlos Cruz, a wildlife biologist with ACT based in Costa Rica.

Cruz specializes in feline ecology and has spent years studying one of nature’s most unique predator–prey relationships: jaguars hunting sea turtles. Only a handful of places in the world still support this dynamic, and in Costa Rica the three known sites are all housed within national parks. This is not a coincidence, but part of a concerted effort by conservationists decades ago. During the 1970s, Costa Rica established its national park system, making the small country the hotspot for biodiversity that it is today. (Prior to co-founding ACT, Liliana Madrigal helped to establish and manage some of Costa Rica’s national parks, including Manuel Antonio National Park).

“These three areas are the way they are right now because there was some intervention,” Cruz said. “Because there was someone in the 70s, 80s saying ‘OK, we’re not going to develop this area.’”

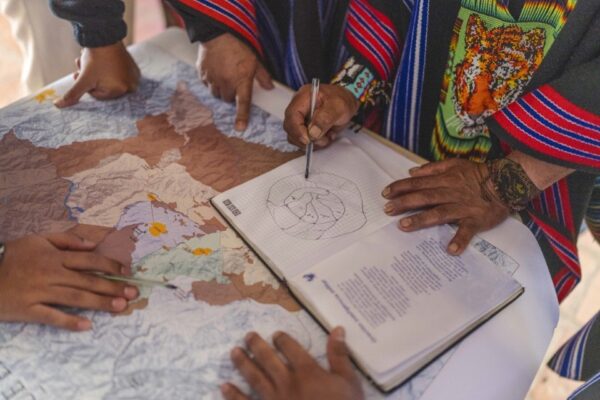

To observe this phenomenon of jaguars moving between forests and coasts, ACT uses camera traps set up at various locations that go off when movement is detected. Cruz also collaborates with the local university to obtain data from GPS collars. While the collars are more invasive because they have to be placed on the animals, they provide a much more comprehensive picture of jaguar behavior and connections in the food web. We now understand, for example, that jaguars come to the Costa Rican coast during sea turtle season.

“It’s an easy meal for them,” said Cruz. “And so that has sustained and has increased the population of jaguars in this area. This is very hard to accomplish.”

The jaguar is the largest cat in the Americas, and there are an estimated 173,000 jaguars currently in the wild. Their habitats, which once spanned from the United States to Uruguay, have declined by about 20 percent since the early 2000s, putting them on the IUCN’s “near threatened” species list. In the last 100 years, we have lost half of the historic distribution of jaguar in the whole continent of South America.

These statistics are concerning from both a cultural and biological perspective. Not only are these highest-level predators critical to ecosystems, they also hold a deep significance for Indigenous communities. For most of the Indigenous peoples that ACT works with, the jaguar is a guardian, and powerful symbol of wisdom.

Glades Kokama, of the Kokama people in Brazil, described her community’s relationship to the jaguar this way:

“For the Kokama people, the jaguar represents the Arcano. The Arcano is protection and ancestry. That is why the jaguar holds such a meaningful place in our spiritual and ancestral life. It symbolizes life and protection — this protection we call the Arcano.

This Arcano is very important, and every community member, every Kokama person, needs to know it. In this experience we are going through now, the jaguar is the being that strengthens our spirit, making it more joyful, more resilient — and it is, without a doubt, the Arcano that protects us.”

For Cruz, these stories deepened his perspective on conservation when he first began working with ACT.

“The first thing I learned—and loved—when I started working with Indigenous communities is that many of them have the jaguar as an icon: an icon of wisdom, an icon of guidance,” he said.

Cruz supports ACT’s Ancestral Tides initiative, which works alongside Indigenous peoples to protect coastal and marine ecosystems. In addition to scientific tools like GPS data and camera traps, he gathers observations from local community members who know the rhythms of their landscapes intimately. These lived accounts confirm that the phenomenon of jaguars hunting sea turtles still occurs in Mexico, Panama, Colombia, and the Guianas as well.

“It’s a clear sign that these two big ecosystems are in balance,” Cruz said.

To maintain this balance against mounting threats like coastal development, and habitat loss, ACT is working to save both turtle and jaguar species. The Ancestral Tides initiative has hatched more than 194,000 sea turtles by protecting nests and coastal habitats from Mexico to Colombia.

But as Cruz, a biologist who chose to work in the conservation field, will tell you, the only way to protect ecosystems is to partner with people.

“I realized gradually that yes, science is important, science is the tool. But the majority, the threats, that you face in the conservation world and endeavors are related to people. You have to work with people.”

Don’t miss these powerful stories and updates. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.