At the airport in Suriname’s capital city, travelers are greeted by a sign beneath a vibrant photo of frogs, parrots, and other rainforest creatures. It reads: “Welcome to Suriname: The most forested country in the world.”

Tucked on the northeastern edge of South America, the former Dutch colony is the continent’s smallest country by both size and population. But what it lacks in scale, Suriname makes up for in cultural and ecological diversity.

For nearly 30 years, the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) has partnered with Indigenous and Maroon communities — descendants of Africans who escaped slavery — to protect Suriname’s vast rainforests. Through our long-running ranger program, we work together to keep Suriname one of the most ecologically vibrant countries on the planet.

Helping lead our community ranger training is Mercedes Hardjoprajitno, Research and Monitoring coordinator for ACT-Guianas. Born and raised in Paramaribo, Mercedes studied environmental science at university before joining Suriname’s forestry service—where she first encountered ACT.

“I found it interesting how they were working with the communities,” she says. “Not only for the protection of the environment, but also for the preservation of culture.”

Since 2007, ACT has helped train more than 60 community rangers and established seven ranger posts across the country. The most recent post opened last month in the Sipaliwini Nature Reserve, near the Brazilian border at a site that is known as Mamija in the Trio Indigenous language. The new station was made possible through collaboration with Re:wild, DOB Ecology, the Suriname Conservation Foundation, and the Global Environmental Facilities Sustainable Landscape Program for the Amazon.

Community rangers in Suriname play a critical role in identifying and reporting illegal and environmentally destructive activities—particularly gold mining, which has surged in recent years due to record-high gold prices. The extent of forest loss from mining is staggering: between 2000 and 2014, the amount of forest converted for mining in Suriname increased by 893%. Gold extraction often leaves behind mercury-contaminated rivers and stripped landscapes, endangering both forest ecosystems and human health.

Mining isn’t the only threat. Logging operations have also led to environmental degradation—especially in regions inhabited by the Matawai Maroons.

“This area was not connected, but the logging company made it accessible because they built a road,” Mercedes explains. “This makes it easier to travel, and for children to go to school,” which she notes is a positive development. “But it also attracts more people to the area, like hunters, which is a growing threat.”

To meet these challenges, ACT trains rangers to support scientific monitoring and environmental research— from testing water quality to tracking wildlife like the jaguar, a key indicator species.

“[The jaguars’] presence or absence tells us how healthy the ecosystem is,” Mercedes says.

Suriname lies within the Guiana Shield, a geological formation in northern South America that coincides with one of the most biologically diverse regions on the planet. Thousands of species—some found nowhere else—call this area home. One example is the bright blue poison dart frog, a species highly vulnerable to habitat disturbance and human activity.

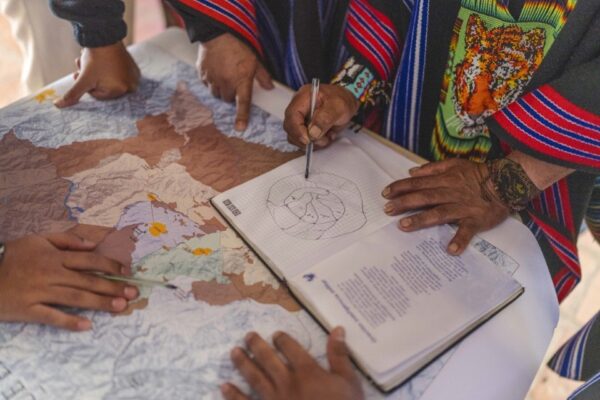

This month, ACT is bringing together knowledge from across the regions where we work. Scientists from ACT-US are in the Guianas helping to teach rangers plant identification and are planning biocultural plant and animal guides in the Wai-wai language. Team members from our Ancestral Tides sea turtle program in Costa Rica are also in the Guianas, collaborating on terrestrial turtle and wolf fish monitoring and research. According to Mercedes, these programs combine modern environmental tools—like GPS devices and camera traps—with traditional Indigenous knowledge to build more effective conservation strategies.

The Amazon Conservation Team works alongside community rangers work to set up camera traps for biological monitoring near the Southern border of Brazil and Suriname. Photo by Juan Carlos Cruz, Amazon Conservation Team

“They already protected based on their traditional knowledge, but with the data that they collect, now you have more evidence to complement traditional stories,” she says.

In fact, local communities often determine where to place camera traps or to search for particular species, based on longstanding ecological expertise passed down across generations.

“We incorporate their traditional knowledge into everything we do,” Mercedes affirms.

As threats to Suriname’s forests continue to grow, ACT’s ranger program—rooted in local knowledge and backed by science—remains a vital force for conservation and educating the next generation of forest protectors. Learn more about our work in the Guianas and how you can support Indigenous and Maroon-led efforts to preserve this extraordinary region.

Share this post

Bring awareness to our projects and mission by sharing this post with your friends.