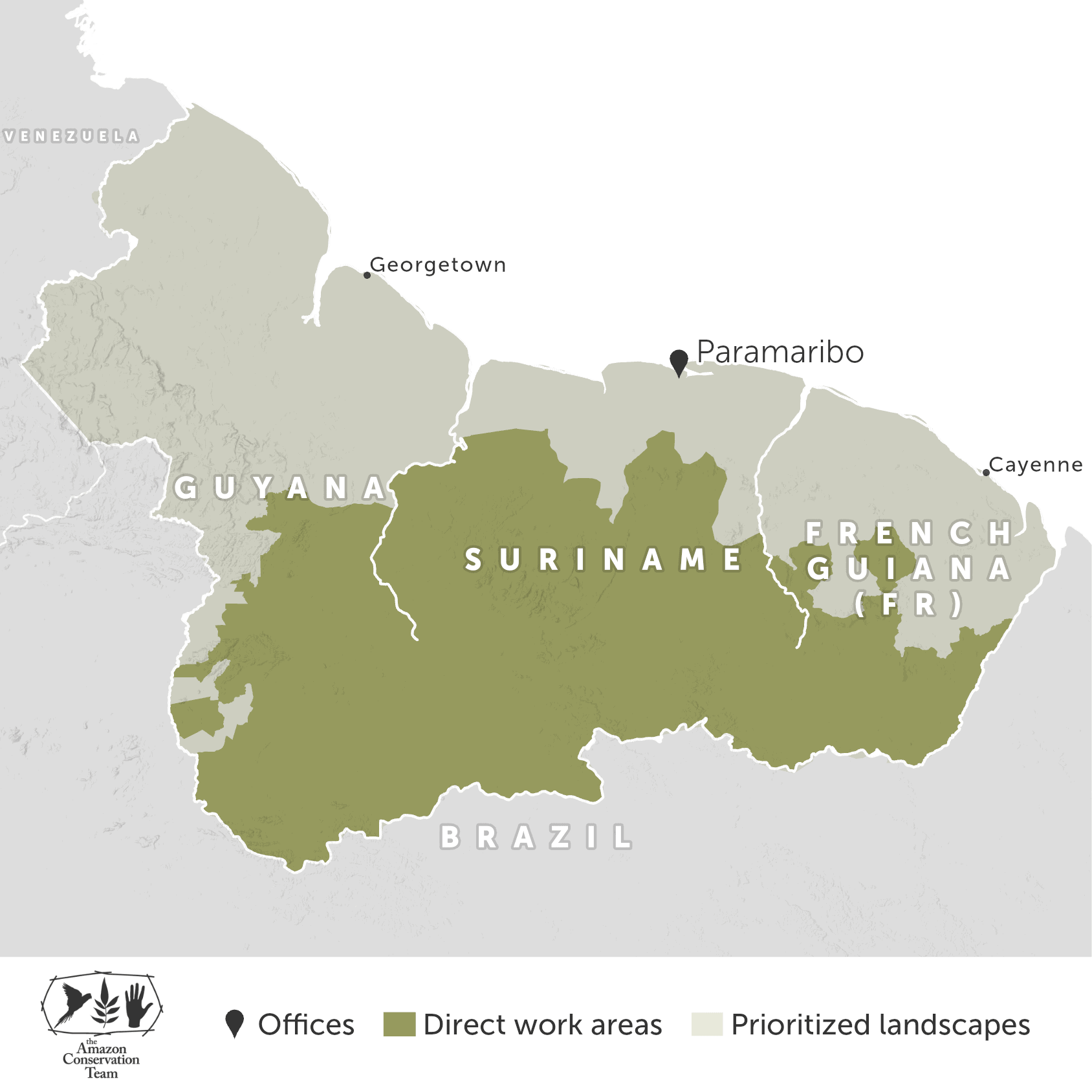

The Guianas – French Guiana, Guyana, and Suriname – are nestled on the northern coast of South America. Due to their complex colonial pasts and unique positioning within the Caribbean, these societies are highly diverse in language, culture, and politics. We work hand-in-hand with indigenous and Maroon communities to protect their ancestral territories and ways of life across the Guianas. We are honored to partner with and work alongside the Trio, Makushi, Waiwai, Wapishana, and Wayana indigenous peoples and the Aluku, Matawai, and Saamaka Maroon peoples.

The ancestral territory of our partners covers a large portion of the Guiana Shield, one of the oldest geological formations on the Earth’s surface and part of the largest remaining block of intact tropical forest in the world. In fact, Suriname is often referred to as the greenest country in the world, with approximately 93% forest cover by some estimates. The Shield is at the center of our long-term transnational initiative to establish a 30-million-hectare biocultural corridor across the eastern Guiana Shield that is managed by and for indigenous and Maroon communities.

LAND:

Protecting biodiversity, tropical forests, and ancestral territory.

Land rights and territorial management: For many indigenous peoples in the Guianas, territory is essential to cultural and physical wellbeing, being intricately linked to food security, medicine, and spirituality. Given this reality, forests are generally better protected when under indigenous management, oftentimes having lower rates of deforestation than national parks. We work at the grassroots level with partner communities and at the institutional level with regional and national governments to secure or uphold collective environmental management and land rights for our partners.

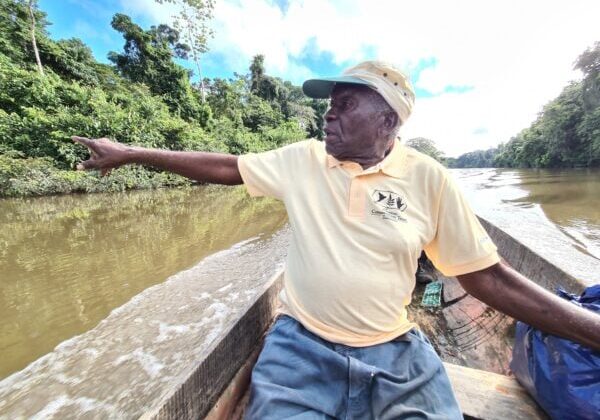

Community environmental monitoring:We support and train indigenous and Maroon community members who carry out environmental monitoring in the forests surrounding their villages. To that end, we facilitate the construction and equipping of ranger stations from which community monitors can track biodiversity and environmental pressures with the latest tools and satellite imagery. This data helps these communities act quickly upon the emergence of crises, such as incursions by illegal miners, and informs internal decisions by traditional authorities on territorial management.Currently, we are providing technical support to community monitors across the Guianas in their effort to more effectively communicate and establish common tools, protocols, and procedures. This transnational collaboration seeks to establish a unified, resilient network that can protect the Guiana Shield in a grassroots manner across national lines.

Participatory mapping: Since 1999, we have facilitated the creation of biocultural maps with many partnering communities in the Guianas. These cartographic tools, developed by the communities themselves, record their history, environmental resources, and traditional knowledge of their territory — and help carry this knowledge to the next generation. These maps also document the extent of their territory and are a critical resource to the communities in advocating for themselves and their ancestral territory before governments and other external entities.

LIVELIHOODS:

Improving physical health, food sovereignty, basic community infrastructure, and economic security to ensure collective well-being.

Sustainable incomes: The production and sale of environmentally sustainable non-forest timber products can generate income to improve the economic security of communities in the most remote rainforest regions. These projects are critical for communities that are integrated into the cash economy and whose members otherwise might have to turn to work in environmentally destructive or illicit industries to make a living. We promote income-generating projects that produce products such as hot peppers, wild herbal tea, honey and medicinal propolis, and handicrafts; these can provide supplementary income that often exceeds regional averages.

Solar energy: Without access to reliable forms of clean energy, many remote communities in the Guianas must rely on gas-powered generators, which negatively impact human health and local environments, and demand unreliable and expensive fuel deliveries. We facilitate the installation of sustainable solar energy systems and train community members in their use and maintenance.

Food sovereignty: We actively partner with communities to bolster their food sovereignty and community nutrition. This work entails maintaining the genetic diversity of local and endemic food species, ensuring the availability of a variety of climate-resilient crops, revitalizing ancestral food production techniques, and reducing dependency on expensive, outside food sources that must be flown into the remote villages.

Intercultural health: For many of our indigenous partners, access to effective intercultural healthcare that is attuned to their specific sociocultural dynamics is a priority. Contemporary Western healthcare systems have historically underserved the unique needs of many indigenous populations, and the imposition of strictly Western healthcare not only has a lower chance of acceptance, but also threatens to further cultural erasure of indigenous health ways and traditional plant knowledge. Therefore, we partner with local healthcare providers and indigenous communities to improve access to preventative and primary medical care that integrates Western and indigenous plant medicine practices.

GOVERNANCE:

Supporting self-determination, human rights, and cultural revitalization.

Community Life Plans: Through the development of a Life Plan, a community envisions their collective future, and builds consensus around topics such as territorial management, preservation of cultural knowledge and traditions, healthcare, and education. The resulting document is an essential tool not only for internal governance and decision-making, but also for advocacy and partnerships with government agencies and the private sector. Inspired by the success of such plans in Colombia and Brazil, we are facilitating the creation of Life Plans with partner communities across southern Suriname.

Indigenous medicine: Part of our founding work, the “Shamans and Apprentices Program” commenced in 1997 and the first associated traditional indigenous medicine clinic was constructed in 1999. These initiatives seek to preserve the transmission and ongoing practice of indigenous plant medicine, based on healers’ encyclopedic knowledge of local flora. To that end, we help communities produce community books on their traditional medicine practices in their native language. We also sponsor apprenticeships where local youth can learn from their community’s healers and help maintain traditional medicine clinics where these practices can continue to be administered.

Cultural revitalization: In the wake of settler colonialism, missionaries, and corporate globalization, the cultural traditions, knowledge, and language of many indigenous peoples were intentionally destroyed or made less prominent in their societies. We partner with indigenous communities in the Guianas in their efforts to preserve, revitalize, and strengthen their living cultural heritage. This goal is carried out through the promotion of cultural exchanges, youth intercultural education, oral history recordings, and indigenous-led media networks.

Related Blog Posts

Testimonials

"As a young community member, being part of the Oral History and Mapping Project was truly empowering. It created a space for us to share our stories, express our wisdom, and recognize the roles we play in preserving our culture and caring for our land.

Having this platform now—something that didn’t exist before—is essential for us as young people. It allows us to learn more about our culture, directly from the knowledge given by our elders.

This experience reminded me of how deeply connected we are to our past, and just how important it is to carry that knowledge forward for the generations to come". - Annalisa Edwards, Moco Moco village, Region 9, Guyana.

Before this land became a protected area, this land was close to threats by gold miners, loggers, and wildlife trappers. The inhabitants of this land were weak in managing their biodiversity. Since our leaders sought ways to protect this land and became a protected area, the size, 648,567.2 HA, we now feel safe with wildlife, animals, and the forest standing. Today we are strongly involved in preservation and protecting this part of Guyana, so that our children can enjoy clean and fresh air in the future, and continue to be the custodians of birds, animals, and the forest of this land". - Joe Daniels, Masakenari village, Guyana

"My name is Faye Mawasha, I am a council member, attached to Masakenari village council.

In this community, there was no proper guest house, only an old rest that was built temporarily, which did not provide accommodation to the standard the visitors expected. In the year 2022, after partnering with ACT, the village was able to get funding to build a new two-story building as a capital project. That is now used as the main guest house. We don't receive any complaints from visitors anymore because we provide better service than before, the building is furnished, and has toilet facilities.

Today, the guesthouse provides job opportunities whenever tourist comes to the village. This facility is one of the sources of income to the community that benefits both the council and villagers". - Faye Mawasha, Masakenari village, Guyana.

"I am a ranger in Amotopo working with ACT. Over the years, I joined several training courses from ACT that helped me improve. Before, I didn’t know how to use a laptop, but now I can use it to register data in our village. I also learned how to install camera traps and collect data. This makes me feel more confident in protecting my village". - Usare Koediman, Amotopo, South Suriname

"My name is Airjian Shodi, a bee technician from Kwamalasamutu, South Suriname. I joined the Stingless Bee Project in 2017 to learn how to produce honey more sustainably, specifically by using hive boxes.

I started with just one box, and now I have nearly 60. I sell honey to local shops and use it as traditional medicine for myself and my family.

In the past, we used to harvest honey from standing or fallen trees, which sometimes meant cutting trees down. Now, we carefully transfer bee hives into boxes, doing our best to avoid felling trees. This method not only helps us protect our forest but also ensures that our bees and the knowledge surrounding them continue to thrive for future generations". - Airjian Shodi, Kwamalasamutu, South Suriname

"I am Jimmy Toeroeman, and I live in Kwamalasamutu. I am the Granman of the Trio people. With support from ACT through different training modules, I can now work in a more structured way on the governance of the Trio tribe. It is important for Indigenous people to have a plan for shaping their future and to speak up about what they believe is right for their village". - Granman Jimmy Toeroemang, Kwamalasamutu, South Suriname

"Over the years, I have participated in several practical trainings that helped me grow. Before, I didn’t know how to use a laptop, but now I can register data from our village independently and send it through email to my station coordinator. I also learned how to install camera traps and collect useful information from the field. These skills have made me more confident in protecting our forest and advocating for the conservation of our ecosystems. Being more aware of my environment has helped me become better equipped to care for our nature and wildlife". - Guillermo Emanuel, Matawai, Central Suriname

"I am Benny Nailoepun from Apetina, a local from the Wayana tribe. My parents taught me to value education and wisdom. I joined the Ranger program and learned about GPS, camera trapping, basic computer skills, and traditional medicine. I became the foreman of the rangers’ team in Apetina and in recent times function as one of the local contact persons (Local assistant) in the village. With the support of ACT, I can also assist in shaping the future of the village by being one of the key persons between the government, NGO's and the village authority of Apetina". -

Jahasoe Nailoepun, Apetina, South-East Suriname